Goryeo Buddhist Paintings and their Transmission to the United States

Over the past five decades, researchers have both defined the nature of Goryeo 高麗 (918–1392) Buddhist painting and identified an expanding number of examples worldwide. This paper is dedicated to the works currently recognized as Goryeo Buddhist paintings in public collections in the United States. It chiefly describes the paths they took to arrive in the US, where they continue to play an important role in efforts to distill the characteristics that distinguish Korean religious images from those made elsewhere in East Asia.

Most of these paintings were once thought to be Chinese or Japanese, and their past owners did not seek them out as Korean works. From early on, the Freer Gallery of Art was a leader in the effort to identify the Korean examples and define the genre. In fact, it appears that the first two Goryeo works identified in the US were in the Freer collection. After the turn of the twentieth century, Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) bought Buddha Amitabha and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas (Figure 2; F1906.269) and Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figure 12; F1904.13) as Chinese works. In 1965, however, James Cahill (1926–2014), museum curator at the time, reassigned them to Korea.1

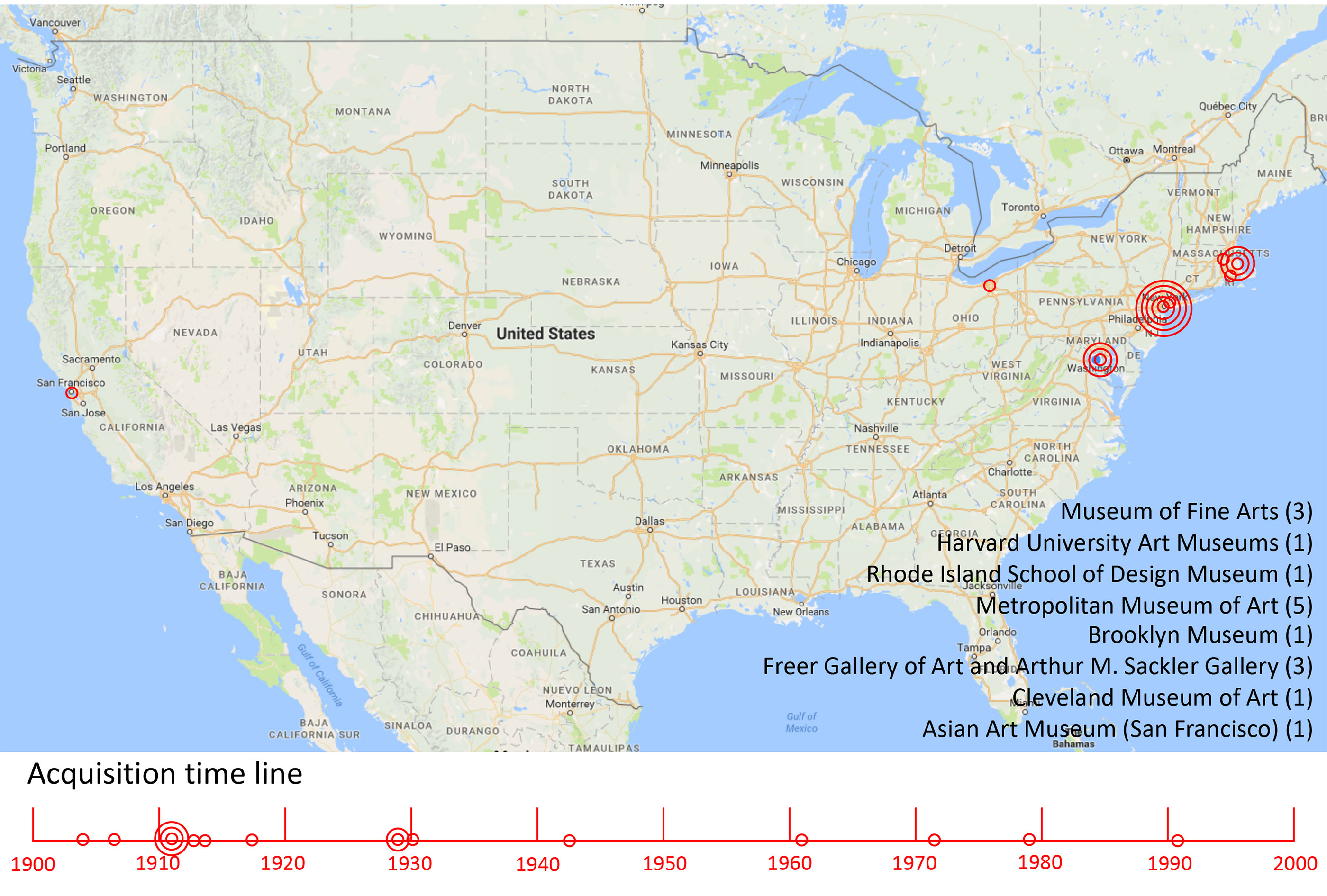

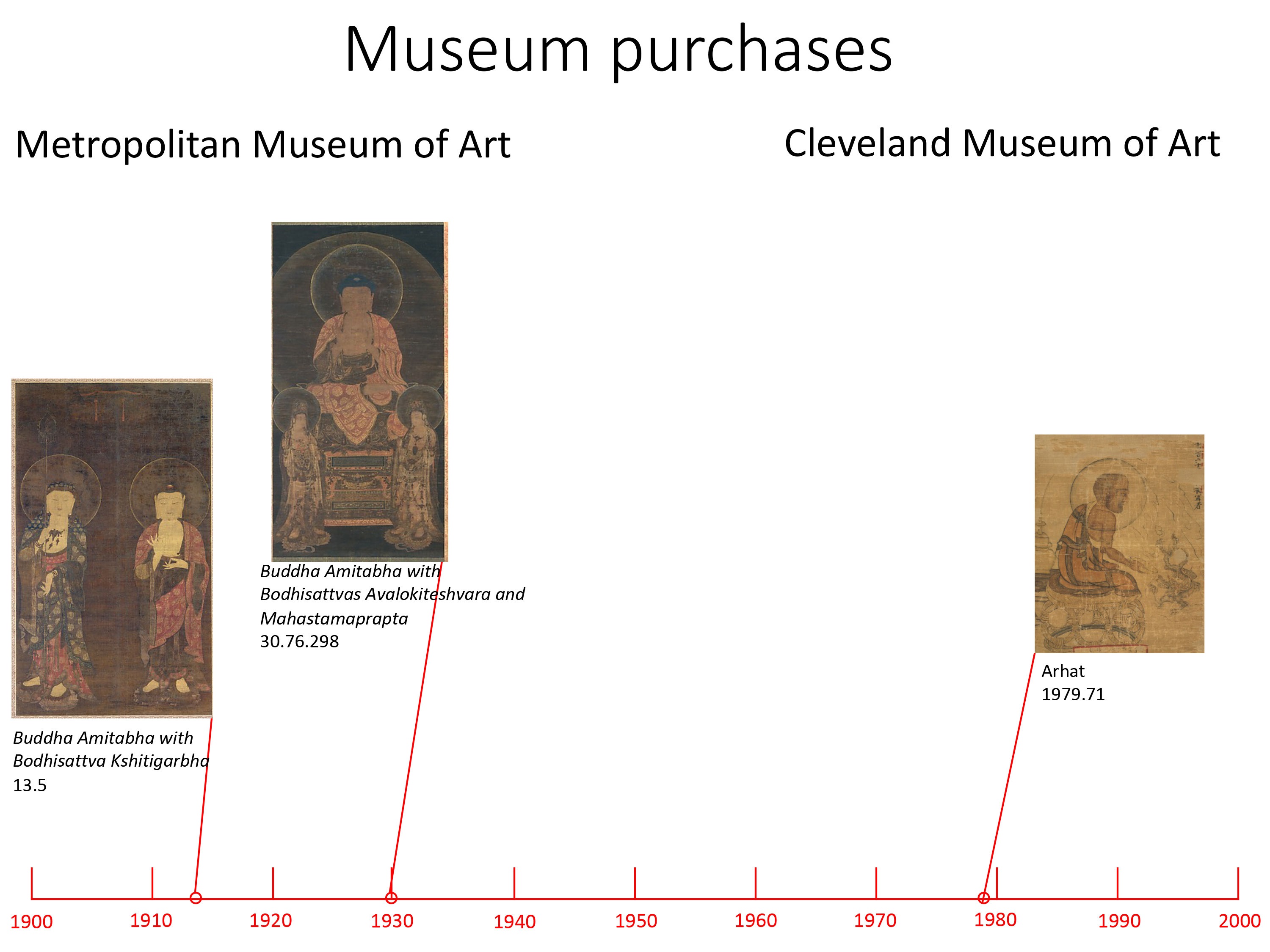

In the decades since the first reattributions, the total number of Goryeo Buddhist paintings recognized in US institutions has risen to sixteen.2 These works are not evenly distributed among museums across the US geographically (Table 1); instead, they are concentrated in the older institutions on the East Coast, especially the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, which together possess eleven of the sixteen works. In Table 1, the timeline below the map indicates that the works were acquired by public collections throughout the twentieth century, but mostly prior to the First World War. They joined museum collections both by donation and museum purchase.

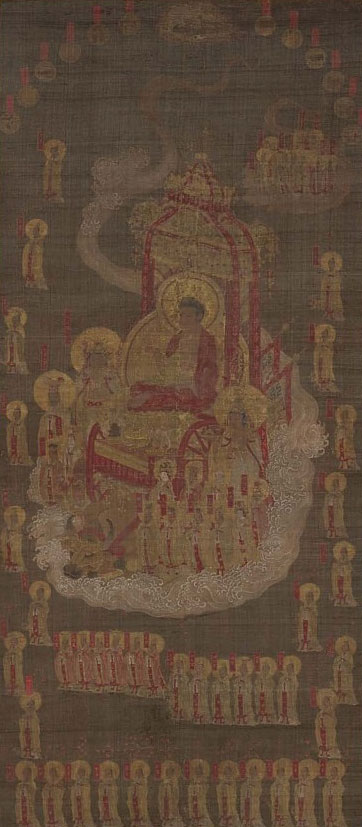

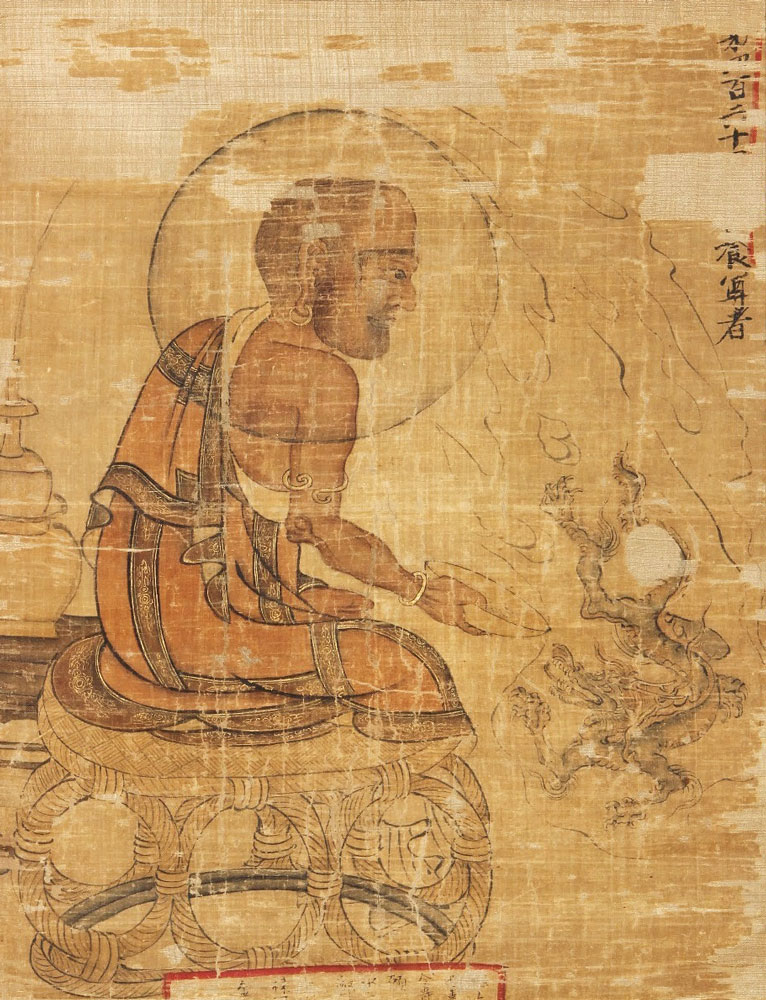

Like Goryeo works now kept in Korea, Japan, and Europe, most of these images reflect Pure Land subjects, such as bodhisattvas with the Buddha Amitabha (Figures 1-5), the bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Figures 5-8), and the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figures 9-13). There are also uncommon iconographies, such as the Buddha of Blazing Light, Tejaprabha (Figure 14; 11.4001), and a preaching Vairochana (Figure 15; 11.6142), both in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Finally, there is a member of the well-known set of Arhat images completed in 1235–1236 (Figure 16; 1979.71).3

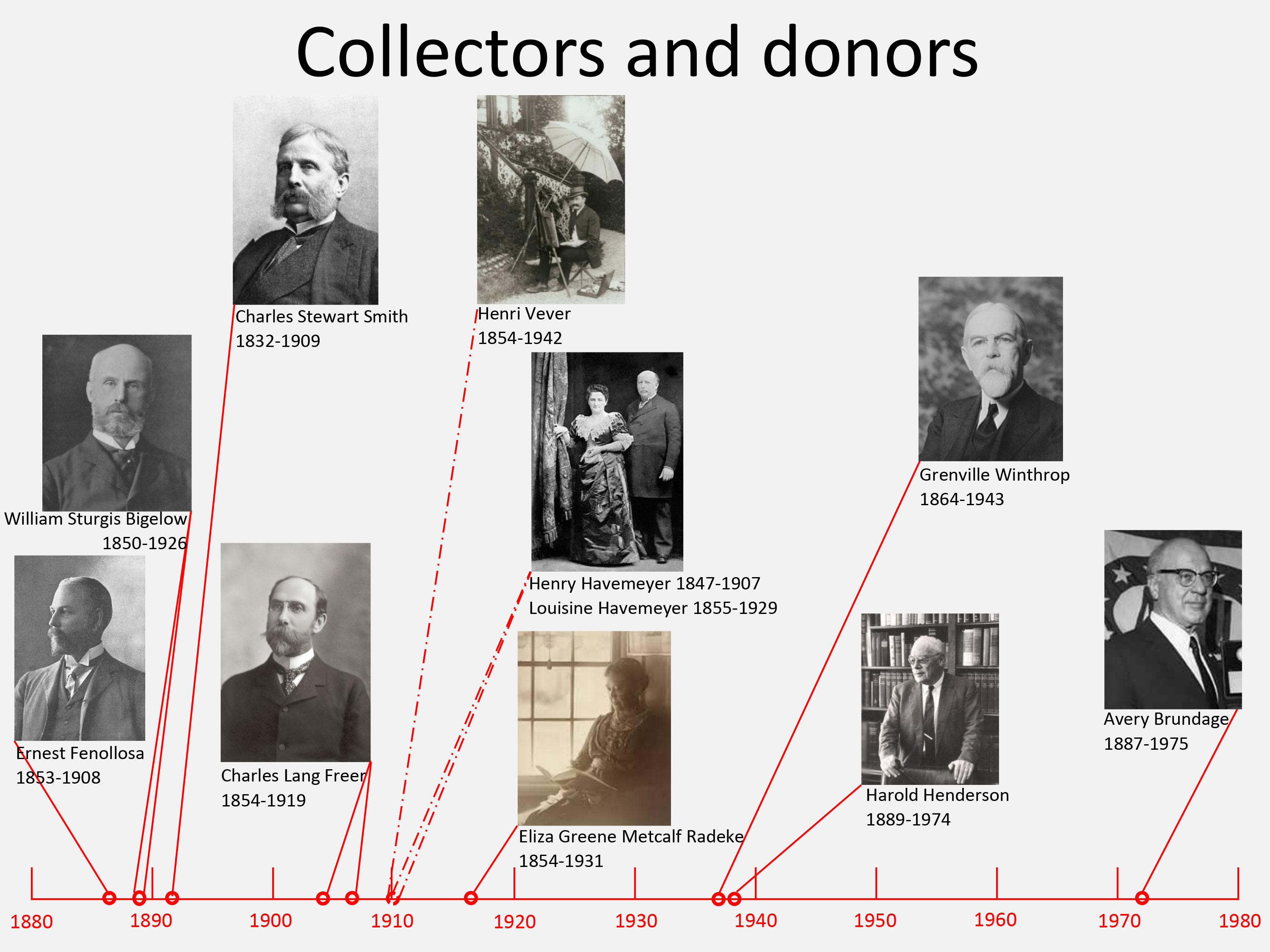

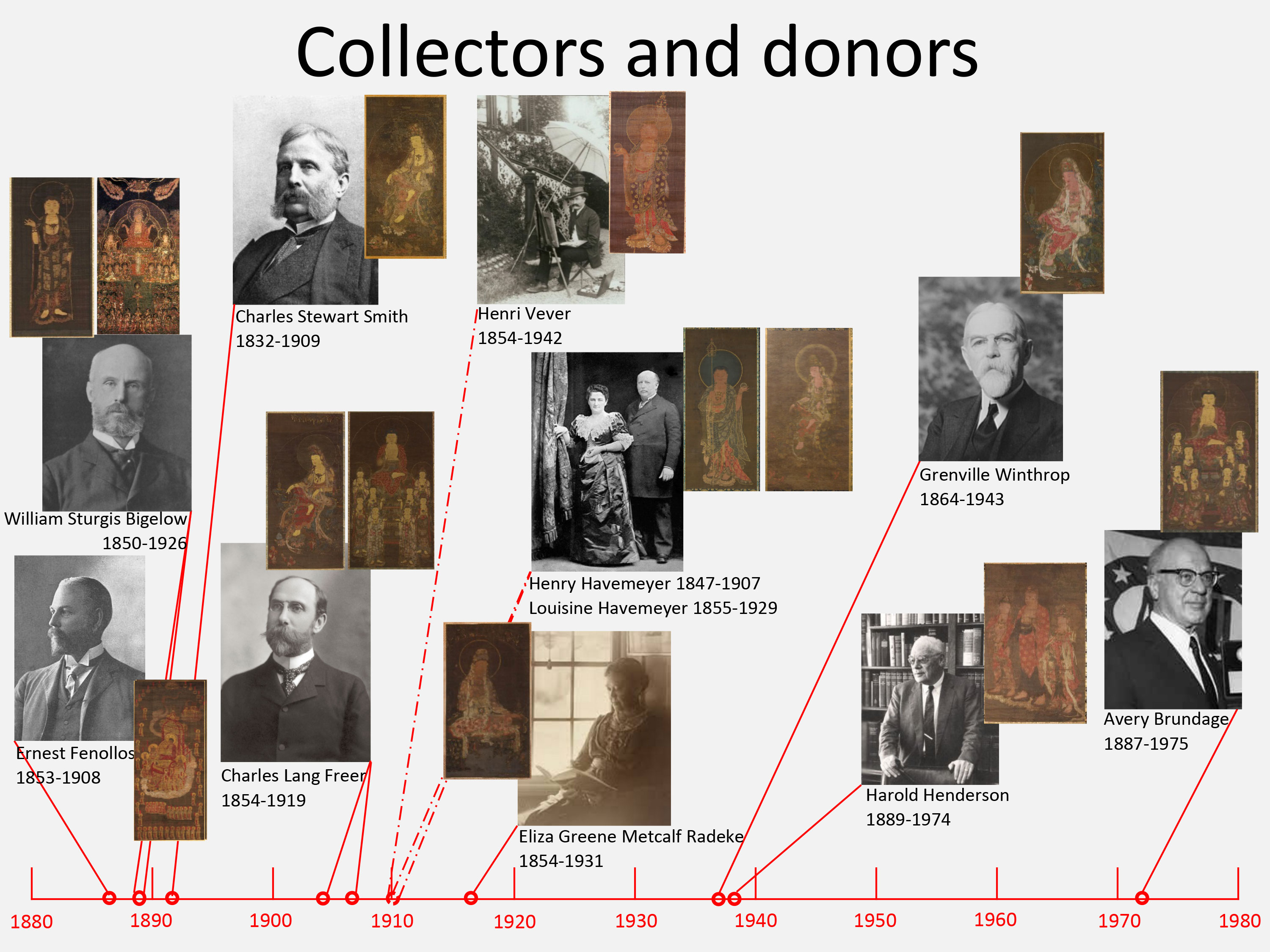

Acquisitions: The thirteen gifts

Thirteen of the sixteen paintings in this study were donations given by American private collectors who owned them first. As will be seen, this group of donors includes some of the earliest and most significant collectors of Asian art in the United States. Table 2 shows these previous owners linked to a timeline to illustrate when they acquired the paintings now accepted as Goryeo. A few of the individuals, like Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) and William Sturgis Bigelow (1850–1926), were chiefly interested in the arts of East Asia, while most, including Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) and the Havemeyers, were attracted to both Asian and Western art, finding important formal or aesthetic connections across place and time.

For the four earliest collectors, cultural interests led to Asian travels that included Japan. In the case of Fenollosa, Bigelow, and Freer, these direct experiences were truly life changing. Most of the later collectors, however, pursued their collecting activities closer to home.

With the exception of Fenollosa and Harold Henderson (1889–1974), who were both academics, these individuals were fantastically wealthy and created enormous collections that profoundly enriched the institutions they created or supported. In most cases, their gifts included thousands of works and spanned media as well as Asian and Western artistic traditions over hundreds or even thousands of years. Only the most recent works purchased by these donors were intentionally acquired as Korean; almost all the others were initially catalogued as Chinese.

The earliest and most influential of these American collectors were Fenollosa and Bigelow—both from Boston and associated with the Museum of Fine Arts—and Charles Lang Freer, an industrialist based in Detroit, who founded his own museum at the Smithsonian. Ernest Fenollosa, who studied philosophy at Harvard, was invited to teach that subject at the University of Tokyo at the young age of twenty-five. He took advantage of the opportunity, ultimately gaining greater fame as a pioneering Asian art historian, as well as becoming a Buddhist. Fenollosa stayed in Japan from 1878 until returning to Boston twelve years later to serve as the first curator in the new Asiatic department at the Museum of Fine Arts. Throughout his adult life, but especially after returning from his second stay in Japan in 1900, Fenollosa lectured widely in America and Europe, and he published many influential books and articles on aesthetics and East Asian art history. He began a close association with Freer in 1901, which strengthened throughout the remaining seven years of Fenollosa’s life.

His compatriot, William Bigelow, a wealthy Boston physician, also traveled extensively in Japan between 1882 and 1889. Like Fenollosa, he became a Buddhist. Together, the two had countless opportunities to view collections and thereby develop a sophisticated understanding of East Asian art history.

The late nineteenth century—especially the 1880s—was a period when large numbers of important early works were being sold by Japanese temples and noble families, supplying a burgeoning international market eager to possess art and understand Asian culture. Fenollosa and Bigelow were well placed to form extremely large collections, and each man succeeded in acquiring numerous significant works.

It is believed that Fenollosa and Bigelow returned to the US with the first paintings now identified as Goryeo. They were bought while the two were living in Japan in the 1880s.4 We do not yet know the source of Fenollosa’s Descent of the Tejaprabha Buddha (Figure 14; 11.4001) or Bigelow’s Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Figure 8; 11.6139), but the Illustration of the Perfect Enlightenment Sutra (Figure 15; 11.6142) can be traced to a specific Japanese temple in Tokyo. This is based on a note found in the roller of the painting in 1907 when it was being restored by the museum. The incident is described in a letter from the curator, J. Arthur MacLean (1879–1964), to a Chicago-based collector named Charles Morse (1852–1911). MacLean states:

A few months ago I had this painting repaired… by our expert here and a most interesting paper was found… It was the memo of the fact that this painting had been repaired about 250 years ago (in 1642 I believe) at the temple of Koriuji [Koryu-ji], Tokyo. This paper gave the names of the different donators and the amounts donated, and was signed by the head priest of the temple.5

Although MacLean’s note doesn’t provide the temple’s name in Chinese characters (kanji 漢字), it seems likely that the painting can be associated with a Nichiren 日蓮 temple called Koryu-ji 幸龍寺 in Setagaya-ku 世田谷区, which has historical ties to Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (1543–1616) and other members of the Tokugawa clan.6 On early (undated) accession file cards, these three paintings collected by Fenollosa and Bigelow are erroneously catalogued as “Chinese, Yuan 元 dynasty.”

Charles Stewart Smith (1832–1909), a prosperous New York retailer and financier, was another prominent late nineteenth-century American who traveled to Japan. A highly respected civic reformer, he was also a strong supporter of the Metropolitan Museum even before it had its first building. In 1892, at the age of sixty, he took his third wife, Anna Walton Brown, to Japan on their honeymoon. While there, he bought a large collection of Japanese graphic arts from Francis Brinkley (1841–1912), the Irish-born owner of the Japan Mail newspaper (the Mail later merged with the Japan Times, which still exists).7 A Goryeo period Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figure 11; 14.76.6) was apparently included amongst the works that Smith purchased on the trip. It is not yet known if it was also bought from Brinkley or if it came from another source in Japan. Upon Smith’s death, most of his Japanese prints and rare books went to the New York Public Library; the remainder of his collection, including the Goryeo painting, was left to the Metropolitan, where he had become a trustee.

Although Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) traveled to Asia several times before and after the turn of the twentieth century, he didn’t purchase the two paintings now identified as Goryeo in Asia. Instead, both came through Paris. His Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figure 12; F1904.13) was similar to the one Smith acquired in Japan. Freer’s version can be traced to 1902, when the Parisian collector Charles Firmin Gillot (1853–1903) purchased it from Yamanaka and Company.8 Gillot, a successful printer who developed the photogravure process, was a member of the artistic circle that surrounded the dealer and art critic Siegfried Bing (1838–1905). Bing was an early promoter of Japanisme and amplified his influence through the popular journal Le Japon artistique, which he published from mid-1888 until 1891.9 Gillot served as the publication director of the serial.

After his death in 1903, Gillot’s large and varied collection was the subject of a much-anticipated series of sales at Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris on February 8–13, 1904, and later in April at the Hôtel Drouot. A total of 3,453 lots were put up for sale.10 Siegfried Bing prepared the sumptuous catalogue. He also personally reviewed the works with Freer in Paris at the end of June, 1903.11 Lot 2004, the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara, was one of the few to be illustrated in the catalogue.12 The entry, which appeared in the Japanese section of the catalogue, described the subject of the scroll using the Japanese term “Kwannon” (or “Kannon”); however, the work was attributed to the Chinese painter Wu Daozi 吳道子 (680–ca. 760), also known as Wu Daoxuan 吳道玄 (the “Gôdo Ghen” referred to in the entry). This may have been based on the traditional attribution of the monumental Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara at Daitoku-ji 大德寺. Freer’s own preliminary notes, perhaps prepared while viewing the work with Bing in Paris, state that the painting may have been copied in Japan during the fourteenth century.

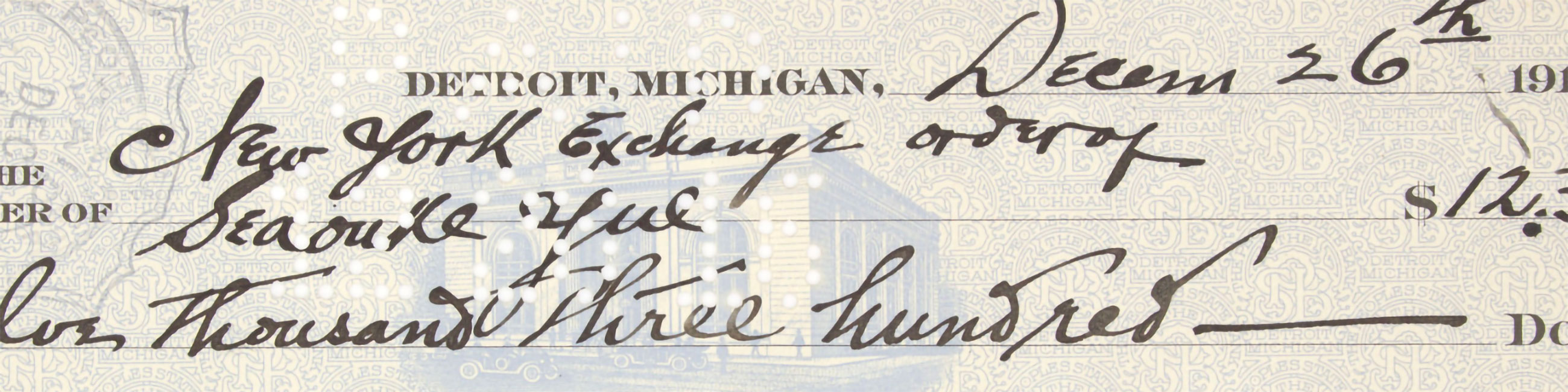

At the sale, Bing served as Freer’s agent and succeeded in buying the Avalokiteshvara for ₣5,900 (roughly $3,300 at the time). By one calculation, this is roughly equivalent to $90,000 today. Two years later, Freer paid $3,500 for his second Goryeo painting (catalogued as Chinese at the time): a larger work featuring the Buddha Amitabha and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas (Figure 2; F1906.269). En route to Europe and his second lengthy stay in Asia, Freer bought it in New York in November 1906 from Yamanaka and Company. This second work came with an attribution to the Song 宋 dynasty (960–1279) artist Zhang Sigong 張思恭 (identified by the Japanese pronunciation of his name, “Cho Shikyo”).

As explained by Yamanaka staff, this work had an impressive history of transmission:

About 30 years ago [ca. 1876], our Mr. Kichirobei Yamanaka [山中吉郎兵衛; ?–1913]13 bought this from the Temple Shojo-shin-in 清浄心院 of Koyasan; about ten years later [ca. 1886] he sold it to Mr. K[enzaburō] Wakai [若井兼三郎; 1834–1908]. When he sold all his collection to Mr. T[adamasa] Hayashi [林忠正; 1853–1906] [in about 1889] this became his possession for his private collection and remained so until the time of his death last spring.14

The temple Shojoshin-in still exists on Mount Kōya, south of Osaka. The individuals mentioned as previous owners were early promoters of Japanese art and culture in Europe, beginning with the World Fairs in Paris. In 1884, Wakai and Hayashi formed a partnership and opened a successful Parisian gallery, becoming Bing’s greatest rivals until the end of the century.

The last members of this early group include the Parisian jeweler Henri Vever (1854–1942), Henry Havemeyer (1847–1907), known as the “Sugar King,” and his wife Louisine Havemeyer (1855–1929), and the second president of the Rhode Island School of Design, Eliza Greene Metcalf Radeke (1854–1931), daughter of the school’s founder. We currently know few details concerning their purchases. Given their friendships and associations, however, it seems safe to assume that they operated within the network that has already been described.

Vever, for example, was a member of Bing’s inner circle in Paris and was a regular at the monthly dinners hosted by Bing and Hayashi for “Les Amis de l’Art Japonais.” Although it cannot be proven, it seems likely that he purchased his beautiful Kshitigarbha image (Figure 6; S1992.11) before Bing’s death in 1905. This work was somewhat out of place in Vever’s collection, which was dominated by illustrated manuscripts, paintings, and drawings from Iran and India. This scroll was given to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery anonymously in 1992.

The Havemeyers were among the wealthiest and most influential art collectors in the US during the Gilded Age, when Henry transformed his family’s already successful business into the massive American Sugar Refining Company, which held near monopolistic control over sweeteners in the eastern half of the United States. Based in New York, the Havemeyers collected broadly and deeply, ultimately giving much of their collection to the Metropolitan. Although they accumulated large numbers of Asian works, they never traveled to Asia. Their gift included two paintings now recognized as Goryeo: Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Figure 7; 29.160.32) and Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figure 10; 29.100.461).15 Unfortunately, the circumstances surrounding their acquisition are currently unknown. It is likely they were purchased prior to Henry’s death in 1907, but that is by no means certain. It is also unclear where they were bought, since the Havemeyers were members of all the major artistic circles in Paris, but also regularly purchased Asian objects from New York dealers, including Yamanaka.

Yamanaka was also a preferred source for Eliza Radeke in her efforts to build the Asian collection of the teaching museum at the Rhode Island School of Design. It seems likely that her stunning Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figure 13; 17.378) was purchased from Yamanaka as well.

The Goryeo works owned by the last three men in the sequence also came directly from Japan, but had remained in the country longer in private collections. For example, the impressive Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Figure 9; 1943.57.12) that New York financier Grenville Winthrop (1864–1943) purchased in 1937 from Yamanaka and Company in New York had previously been owned by the powerful Japanese entrepreneur Go Seinosuke 郷誠之助 (1865–1942). It is now in the Harvard University Art Museums.

One year later, Harold Henderson (1889–1974), a curator at the Metropolitan Museum (1927–1929) before becoming a professor at Columbia University (1934–1956), found his Amitabha Triad (Figure 4; 61.204.30) during a sabbatical spent in Japan. Stickers on the box suggest that it had previously been sold by the Kyoto-based dealer “G. Kitanaka.”

Finally, Avery Brundage (1887–1975) found his Buddha Amitabha and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas (Figure 1; B72D38) at the Tokyo dealer Mayuyama 繭山. It was gifted to the Asian Art Museum in 1972. The work was listed as Goryeo in the chronicle of 1972 museum acquisitions published in Archives of Asian Art and included in the celebratory volume Mayuyama Seventy Years, making it the first of our paintings purposely purchased as Korean.16

Acquisitions: The three purchases

A few years after Brundage became the first of the American collectors to intentionally purchase a Goryeo work, the Cleveland Museum of Art made a pioneering purchase of a Goryeo Buddhist painting, signaling a recognition of the art historical significance of the genre (Figure 16; 1979.71; Table 4). It was a smart and safe acquisition since the painting belonged to a set of works that was already documented as having been painted in Korea during the thirteenth century. This work also came from a Japanese dealer. Its time in Japan was confirmed by a peculiar detail: A round loss near the rear legs of the dragon seems to be the result of a hand pull (hikite 引手 ) that was added when the painting was mounted on a sliding panel.17 The repurposing of the painting to decorate a typical piece of Japanese furniture is an unusual aspect of the painting’s transmission.

The two remaining Goryeo works were purchased by the Metropolitan Museum as Chinese paintings earlier in the twentieth century. Few details associated with the 1930 acquisition of an Amitabha triad are known (Figure 3; 30.76.298). An unusual painting showing the Buddha Amitabha with the Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Figure 5; 13.5), however, was discovered in Japan by one of the museum’s early curators of decorative arts, Garrett Chatfield Pier (1875–1943). Although he may not have known it at the time, he chose a particularly rare painting illustrating an exceptional composition.18 The English-born Pier, who worked briefly at the Met, is better remembered as an Egyptologist, forming his own collection of antiquities in addition to the one he helped build at the museum. He also traveled to East Asia at least once, inspiring his publications on the mortuary temple of the Yongle 永樂 emperor (1360–1424) in Beijing as well as Temple Treasures of Japan, an engaging guide to Buddhist temples.19

Conclusion

The sixteen works featured in this study possess numerous common characteristics. All appear to have been acquired by their American purchasers from a Japanese source—half were bought in Japan and at least another quarter came from Yamanaka & Company in New York. Aside from the two examples that were intentionally acquired as Korean works in the 1970s, the paintings were pre-War purchases. Four are known to have left Japanese temple collections in the 1880s, including two that can be traced to specific temples in Tokyo and on Mt. Kōya. There are surely additional paintings in the group that left temple collections as a result of the economic and cultural change associated with the Meiji 明治 period (1868-1912).

Sadly, we have no way of knowing how and when the works arrived in these temples. When acquired by their American owners, the pre-War purchases were generally believed to be Chinese works of art. Some bore attributions to specific artists, chiefly the famous Tang dynasty (618–907) painter Wu Daozi or the Song painter Zhang Sigong, who is virtually unknown aside from the specific body of Buddhist paintings now known to be Korean that can be traced to Japanese temple collections. In fact, at least four of the paintings in US collections bear attributions to this mysterious painter, mainly in the form of inscriptions written on their storage boxes. As pointed out by Yukio Lippit:

It is clear from…early twentieth-century publications…that early Korean hanging scrolls were being understood as works of Chinese manufacture. More specifically, they were increasingly being grouped under the rubric of the “Zhang Sigong style”…Under the sway of this taxonomy, overseas collectors in the early years of the twentieth century often purchased Goryeo Buddhist paintings under the assumption that they were obtaining a scroll by a Chinese master.20

The thoughtful reevaluation of these traditional attributions began in the mid-1960s when the two paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art were reassigned to Korea. Several other works in the Metropolitan and Brooklyn Museums were reattributed within a decade.

In conclusion, we can say that these sixteen works reflect the twentieth-century pattern of Asian art collecting in the US:

- They were largely acquired in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century

- The most highly respected collectors of Asian art at the time were attracted to the beauty of these works

- These collectors were drawn to the more decorative images of single figures, especially Avalokiteshvara

- Six were purchased when their owners were traveling in Japan

- Four, if not more, of the remainder can be traced to Yamanaka and Company

- Two can be associated with specific temples in Tokyo and on Mount Kōya

- The financial value of the works can be bench-marked by Freer’s payments of around $3,500 for his purchases in 1904 and 1906, roughly equivalent to $90,000 today

Notes

[1] The reattributions are documented in the museum’s permanent record, the Freer “Folder Sheets,” which have also been transferred to the digital files in the collection database. To be accurate, Cahill dated only Buddha Amitabha and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas to the fourteenth-century Goryeo period; he placed the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara slightly later, “Korea Yi dynasty, 15th century.” It is now also recognized as a Goryeo work.

[2] See Kikutake Junichi 菊竹淳一and Chung Woothak 鄭于澤, eds., Koryo sidae ui bulhwa 高麗時代의 佛畵 [The Buddhist painting of Koryo Dynasty] (Seoul: Sigongsa, 1997); and Kikutake Junichi 菊竹淳一and Chung Woothak 鄭于澤, eds., Korai jidai no butsuga 高麗時代の仏画 [The Buddhist painting of Koryo Dynasty] (Seoul: Sigongsa, 2000). These are supplemented by Chung Woothak 정우택, “Miguk sojae Hanguk bulhwa josa yeongu 미국소재 한국불화 조사 연구 [Investigation Research on the Korean Buddhist Painting in the United States],” Dongak misulsahak 東岳美術史學13 (2012): 33–63.

[3] The monumental Shakyamuni Triad in the Cleveland Museum of Art (1982.25) was the centerpiece of a triptych that included depictions of the bodhisattvas Samantabhadra and Manjushri, now in the Seikadō Bunko in Tokyo. It was purchased as a Korean painting but is now described as a Chinese image of the Yuan or early Ming dynasty and thus will not be included in this essay.

[4] In 1886, before returning to Boston, Ernest Fenollosa—never a wealthy man—sold his collection to Charles Goddard Weld (1857–1911), a Boston-area physician and philanthropist, with the stipulation that it enter the Museum of Fine Arts after Weld’s death. Thus, the Boston museum’s formal acquisition date given to the Fenollosa collection is 1911, well after Fenellosa’s death; Weld is also named in the credit line.

[5] A copy of the letter, dated November 21, 1907, is in the object file at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[6] I would like to thank Frank Feltens (Freer|Sackler) for helping me identify this temple.

[7] Brinkley moved to Japan in 1867 and stayed for over forty years.

[8] The Yamanaka source for the painting is based upon a note that was acquired with the painting.

[9] For an introduction to this serial, see Gabriel P. Weisberg, “On Understanding Artistic Japan,” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 1 (Spring 1986): 6–19.

[10] Galeries de Durand-Ruel, Collection Ch. Gillot: Objets d'art et peintures d'Extreme Orient (Paris: Galeries de MM. Durand-Ruel, 1904).

[11] Entries from Charles Lang Freer Diary, June 25 and June 27; see also a letter to Siegfried Bing dated August 26, 1903, Freer|Sackler archives.

[12] Galeries de Durand-Ruel, Collection Ch. Gillot, 223, 266, lot 2004.

[13] Kichirobei Yamanaka (died 1913) was the adoptive father of Adachi (Yamanaka) Sadajiro (1866–1936), founder of the Yamanaka and Company office in New York in 1893. The younger Yamanaka was also his son-in-law since he married Yamanaka Tei, his adoptive father’s daughter, in 1889. See Sonoko Monden, "Yamanaka Sadajirō (1866–1936)," in BRITAIN & JAPAN: Biographical Portraits (Leiden, The Netherlands: Global Oriental, 2013), 278–79, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004246461_022.

[14] Purchase record for F1906.269; Freer|Sackler Archive.

[15] Neither of these works were originally included in the Havemeyer bequest to the Metropolitan; they were added at the request of the museum’s curators.

[16] Mayuyama Junkichi 繭山順吉, Ryūsen shūhō: Sōgyō shichijusshūnen kinen 龍泉集芳: 創業七十周年記念 [Mayuyama, Seventy years] (Tōkyō: Mayuyama Ryūsendō, 1976), vol. 2, cat. no. 257.

[17] This observation was made by Jennifer Perry, a former conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art and kept in the object files.

[18] In his catalogue entry for this painting, Yukio Lippit observes: “The pairing of Kshitigarbha with Amitabha here is unique among extant Goryeo-period paintings. Conservation of the scroll has confirmed that the two deities are depicted on separate pieces of silk, indicating that originally they may have been on two separate scrolls, perhaps as part of a triptych.” See Kumja Paik Kim, Goryeo Dynasty: Korea’s Age of Enlightenment, 918–1392 (San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, 2003), 73.

[19] Garrett Chatfield Pier, “The Mortuary Temple of Yung-Lo Near Peking,” Art and Archaeology: An Illustrated Magazine 1 (1914), 103–111; and Temple Treasures of Japan (New York: F. F. Sherman, 1914).

[20] Yukio Lippit, “Goryeo Buddhist Paintings in an Interregional Context,” Ars Orientalis 35 (2008), 201–202.

Bibliography

Chung Woothak 정우택. “Miguk sojae Hanguk bulhwa josa yeongu 미국소재 한국불화 조사 연구 [Investigation Research on the Korean Buddhist Painting in the United States].” Dongak misulsahak 東岳美術史學 13 (2012): 33–63.

Galeries de MM. Durand-Ruel. Collection Ch. Gillot: Objets d'art et peintures d'Extreme Orient. Paris: Galeries de MM. Durand-Ruel, 1904.

Kikutake Junichi 菊竹淳一 and Chung Woothak 鄭于澤, eds. Kōrai jidai no butsuga 高麗時代の仏画 [The Buddhist paintings of Koryo Dynasty]. Seoul: Sigongsa, 2000.

Kikutake Junichi 菊竹淳一 and Chung Woothak 鄭于澤, eds. Goryeo sidae ui bulhwa 高麗時代의 佛畵 [The Buddhist paintings of Koryo dynasty]. Seoul: Sigongsa, 1997.

Kim, Kumja Paik. Goryeo Dynasty: Korea’s Age of Enlightenment, 918–1392. San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, 2003.

Mayuyama Junkichi 繭山順吉. Ryūsen shūhō: Sōgyō shichijusshūnen kinen 龍泉集芳: 創業七十周年記念 [Mayuyama, Seventy years]. Tōkyō: Mayuyama Ryūsendō, 1976.

Monden, Sonoko. "Yamanaka Sadajirō (1866–1936)." In BRITAIN & JAPAN: Biographical Portraits. Leiden, The Netherlands: Global Oriental, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004246461_022.

Pier, Garrett Chatfield. “The Mortuary Temple of Yung-Lo Near Peking.” Art and Archaeology: An Illustrated Magazine 1 (1914): 103–111.

Pier, Garrett Chatfield. Temple Treasures of Japan. New York: F. F. Sherman, 1914.

Weisberg, Gabriel P. “On Understanding Artistic Japan.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 1 (Spring 1986): 6–19.