Mesopotamian Cylinder Seal Inscriptions

Ancient Near Eastern seals are best known for their wide iconographic repertoire, from geometric designs to animals to human figures to scenes. However, on occasion, the seals also contained writing. In Mesopotamia, the inscription was written using the cuneiform script. Cuneiform, one of the earliest known writing systems, is characterized by its wedge-shaped marks. The inscription, known from either the physical seal itself or its impression in clay, contained different types of information, which, in combination with the context in which the seal was used, gives us insights into the lives and cultural practices of the people who utilized them. The type of information found on a seal, the significance of the information, and whether there is a relationship between the inscription and the image on a seal will be discussed using examples from the Sargonic (2334–2154 BCE), Ur III (2112–2004 BCE), Old Babylonian (2000–1600 BCE), and Kassite (1595–1155 BCE) periods.

Type of Information Contained in a Seal’s Inscription

What kind of information is found in the inscription on a seal? This varies depending on the time period. Seals from the Sargonic period have different types of inscriptions. Some have just the owner’s name, others have “personal name, scribe,” and a third group are of the type “personal name, profession (other than scribe).” These groups of seals vary widely in quality (how well the seal was cut) and subject matter of the image. A seal made of greenstone, now in the British Museum (BM 89115) identifies the owner of the seal as:

Adda

scribe

During the Old Babylonian period, three pieces of information were normally included: the owner’s name, his father’s name, and the name of the deity that the owner served.1 A seal impressed on a fragment of a letter envelope found at Number 7 Quiet Street in the city of Ur, an important city-state in southern Mesopotamia located near the Persian Gulf, reads:

Waqrum

son of Shamash-naṣir

servant of Nimintabba2

At Ur, Nimintabba was a minor female deity, one of the “standing gods” at the temple of Sîn who were responsible for guarding the libations and food offerings.3

During the Kassite period, while seal inscriptions could contain information similar to that of seals from the Old Babylonian period, they could also contain prayers, which generally ask for protection for the owner of the seal. The prayer could be general, as in one seal from Thebes now in the Archaeological Museum of Thebes (no. 30):

At the word of Marduk

May its [the seal’s] bearer remain in good health.4

Another seal in the same collection (no. 32) is more specific:

Ninlil, lady of the lands,

in the bed of (the one who holds) the status of the head of your household,

in the chamber of your (sexual) charms,

with Enlil, [your?] beloved,

intercede for me,

the shatammu-official of Ninmah,

Mili-Shipak.5

Although the owner of the seal, Mili-Shipak, serves in a professional capacity in the temple of Ninmah (one of the mother goddesses), he appeals to the goddess Ninlil to intercede on his behalf with her husband, Enlil, who is one of the supreme gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon.

Significance of the Information on a Seal

What can the information contained on a seal tell us? During the Old Babylonian period a person’s name, his father’s name, and an entity that the person was devoted to was the essential information about an individual’s identity. If the entity that the person was devoted to was a deity, the deity would have usually been a minor deity who was worshiped in the neighborhood or part of the city in which the owner lived, giving that person a local identity.6 It would be inaccurate to call the deity someone’s “personal god,” however. An individual did not pick a god to worship; this would have been the same god that his father, grandfather, and other ancestors also worshiped. One example comes from the city-state of Nippur. Both Imgur-Sîn and his son Ipqu-Damu are identified as servants of Damu, a god of healing.7

Old Babylonian cylinder seal belonging to Iddin-Shamash. Freer Gallery of Art, F1993.18.2. Gift of the Duncan M. Whittome Revocable Trust in memory of Ambassador and Mrs. James S. Moose, Jr.

The hematite Freer Gallery cylinder seal F1993.18.2 provides a contrast to the seal belonging to Waqrum described above. It reads:

Iddin-Shamash

Son of IZ-ZA-AK-KA-AN

Servant of Shamshi-Adad

Here, the inscription identifies the owner of the seal, Iddin-Shamash, his father’s name (IZ-ZA-AK-KA-AN), and the one he serves (Shamshi-Adad). Based on the style of the images on the seal—a female deity appearing as a supplicant before a royal figure—Shamshi-Adad probably refers to Shamshi-Adad I, who ruled various parts of northern Mesopotamia from 1809 to 1776 BCE. Here, Shamshi-Adad, a king, takes the expected place of a deity as the one whom the owner of the seal served. Were kings thought to be divine?8 In Mesopotamia, while all kings were considered sacred, divine kingship was a rare phenomenon and came about as a result of highly specific historical circumstances. Naram-Sîn, the fourth king of the Dynasty of Akkade (2334–2154 BCE), was the first self-proclaimed divine king. He had himself declared divine shortly after the so-called Great Rebellion, which threatened the Akkadian Empire.9 Divine kingship didn’t appear again until the Ur III period. King Ur-Namma was mortally wounded in battle, which would have been considered a cosmic tragedy because it indicated divine displeasure and the king’s loss of favor with the gods. Ur-Namma’s successor, Shulgi, was able to hold the kingdom together by reinventing himself as the brother of the legendary king Gilgamesh, who was himself the son of the royal hero Lugalbanda and the goddess Ninsumuna, and a few of Shulgi’s successors continued the tradition of divine kingship.10

So what does it mean, then, that an individual was a “servant” of a deity or a king? This designation gives us information about cultural practices during this time. One possible interpretation is that “servant” is a professional affiliation. In this understanding, the owner would be a part of the temple bureaucracy in the same way that the servant of a king would belong to the palace administration. Another interpretation is that “servant” indicates an individual’s personal devotion. Evidence for this latter interpretation comes from a seal impression on an Old Babylonian contract, TCL 1, 69 from the Louvre, which reads:

Shalim-palih-Marduk

Son of Sîn-gamil,

shangûm of Shamash,

Servant of Marduk

Here, Shalim-palih-Marduk is identified as both the shangûm of Shamash (his profession—a shangûm works in a temple, in this case, the temple of Shamash, the sun god) and as a servant of Marduk, the city god of Babylon. Thus, since he has a professional affiliation to one deity, Shamash, and is also identified as the servant of another deity, Marduk, “servant of” cannot also indicate a professional affiliation and must therefore indicate some sort of personal devotion.11 The fact that an individual could be identified as both a servant of a king and a servant of a deity also supports this interpretation, since it is unlikely that an individual could work in two such different professional capacities at the same time. On one seal impression, Balmunamhe, the son of Sîn-nur-matim, is identified as the servant of Warad-Sîn, who ruled the city-state of Larsa from approximately 1770 to 1758 BCE.12 On another seal impression, Balmunamhe is identified as the servant of the god Enki and another deity whose name is missing.13 The name of this missing deity is probably Damgalnunna, Enki’s wife. Thus, while a “servant” of a deity has a personal devotion to that deity, a “servant” of a king may in fact work as part of the palace administration.

During the earlier Sargonic period, these seals that indicate a devotion to a king would have come from the king to the official rather than being an expression of devotion on the part of the official.14 These seals, which have inscriptions of the type “royal name, personal name, his servant/your servant,” are all of high quality and contain a narrow range of images: the standard Sargonic combat scene (two pairs of combatants on both sides of the inscription), non-combatant pairs on either side of the inscription, or a presentation scene in which a human figure is presented by one deity to another (presumably higher ranking) deity. Unlike seals that bear only personal names, where some inscriptions were clearly added after the seal was made, the inscriptions on this group are well planned.15 One seal inscription in the Louvre (Fig. 2) reads:

Sharkalisharri

strong

king

of Agade

Tudasharlibish

beloved

of the king

Dada

shabra of the house

son of . . .

Impression of Sargonic period seal presented to Dada. Louis Delaporte and F. Thureau-Dangin. Catalogue des Cylindres, Cachets et Pierres Gravées de Style Oriental Musée du Louvre. Paris: Hachette, 1920. Pl. 9: 11a. Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The image contains a man standing before a seated woman, who is depicted on a much larger scale than the man. The inscription is written in four separate boxes or cases. The case containing the name Tudasharlibish, who is the wife of Sharkalisharri, is placed directly behind the seated woman, while the case containing the name Dada is behind the man. This very carefully planned seal seems to depict the relationship between the seal owner and the woman he serves.

Studying groups of seals or seal impressions can also tell us more about the owner of the seal. On occasion, we have evidence that an individual made use of more than one seal in his or her lifetime. During the Ur III period, this could happen in two circumstances: 1) if an individual to whom a seal was dedicated died or retired; 2) if the owner of the seal advanced in his career and his position or profession changed.16 For example, Ur-Lisi used at least two different seals.17 One is dedicated to Shulgi (reigned 2094–2047 BCE).18 The other is dedicated to Amar-Sîn (reigned 2047–2038 BCE).19 Since Ur-Lisi was the governor of Umma—an important city in southern Mesopotamia—from the thirty-fifth year of Shulgi’s reign to the eighth year of Amar-Sîn’s reign, it is apparent why he needed the different seals.

One particularly interesting set of seals belonged to Ninḫilia, the wife of Ayakala, the man who succeeded Ur-Lisi as governor of Umma. Before her husband became governor, her seal identified her as “Ninḫilia, wife of Ayakala, son of Ur-Damu,” while her later seal identified her as “Ninḫilia, wife of Ayakala, ensi [governor] of Umma.”20 These seals are known from their impressions on various documents from this period.21 Ninḫilia sealed these documents on receipt of various goods, including wool, dyes, cedar, fragrances, leather, chairs, and shoes.22 These documents suggest that she was engaging in important economic transactions even before her husband became governor. Women could also hold other important positions. For example, we know that Shulgi-simti, wife of King Shulgi, was in charge of managing a livestock park at Puzrish-Dagan.23

The information on the seal can also inform us about sealing practices. Under certain circumstances, someone other than the owner of the seal used it to seal documents. During the Ur III period, a letter explained that it was not sealed as expected because “the seal of the sukkal-mah (chancellor) was not available.”24 This implies that a subordinate could use his superior’s seal when acting on his superior’s behalf.25 An individual could also use a seal belonging to a relative. During the Old Babylonian period, a scribe by the name of Sîn-nadin-shumi used the seal of his father, Ipiq-Aya, before finally acquiring a seal of his own.26

Sometimes, however, the significance of the information contained in the inscription is unclear. One unpublished seal in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (A207911) simply contains the names of two deities: Nusku and Ninshubur. There is no apparent relation between the two deities on the seal, however. Both are minor deities that function as ministers to more important deities (Nusku to Enlil and Ninshubur to Ishtar). Thus, the reason for the mention of Nusku and Ninshubur on the seal is uncertain.

Old Babylonian cylinder seal impression. Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, A207911. Photo by: Antonietta Catanzariti

Is there a relationship between the image on the seal and the text?

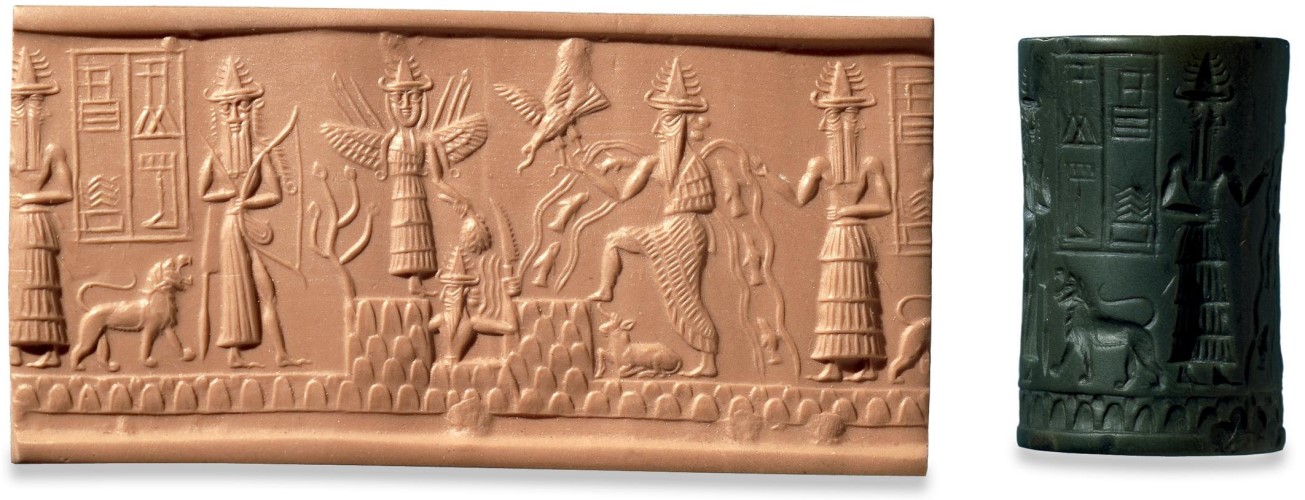

In general, there appears to be very little correlation between the image on the seal and the inscription. In the seal belonging to Adda (Fig. 4), several deities are depicted: an unidentified hunting god, a winged Ishtar, Shamash (the sun god) rising from between two mountains, Enki (the god of underground water and magic) with streams of water containing fish coming out of his shoulders, and Isimu, Enki’s two-faced minister. It is unclear what connection, if any, Adda had to any of the gods.

Sargonic period seal belonging to Adda. British Museum, BM 89115. © The Trustees of the British Museum

“Presentation seals”—seals presented by a king to an individual—however, are a narrow category of seals that might be an exception in having a connection between the image on the seal and its inscription. These seals list the name and titles of the king, the individual to whom it was presented, and the statement “to his servant, he presented.” In general, these seals depict both the king and the owner of the seal.27 For example, the seal impressed on one tablet identifies the seal as having been presented to Babati by the king Shu-Sîn (reigned 1972–1964 BCE).28 The image appears to be of an individual standing in front of a seated king.29

Our knowledge about inscriptions on seals is not uniform across time and space; a lot of work remains to be done. The little information that we do have about seal inscriptions, however, gives us a tantalizing glimpse into the lives, culture, and practices of people in the ancient Near East.

Bibliography

Brinkman, J. A. “The Western Asiatic Seals Found at Thebes in Greece: A Preliminary Edition of the Inscriptions.” Archiv für Orientforschung 28 (1981/82): 73–77.

Charpin, Dominique. Le clergé d’Ur au siècle d’Hammurabi. Geneva and Paris: Libraire Droz, 1986.

———. “Les Divinités Familiales des Babyloniens d’après de leurs sceaux-cylindres.” In De la Babylonie à la Syrie en passant par Mari. Mélanges offerts à Monsieur J.-R. Kupper à l’occasion de son 70e anniversaire, edited by Ö. Tunca, 59–78. Liège: University of Liège, 1990.

Franke, Judith A. “Presentation Seals of the Ur III/Isin-Larsa Period.” In Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, edited by McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs. Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1977.

Michalowski, Piotr. “The Mortal Kings of Ur: A Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia.” In Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond, edited by Nicole Brisch. Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 2008.

Parr, P. A. “A Letter of Ur-Lisi, Governor of Umma.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 24 (1972): 135–36.

———. “Ninḫilia: Wife of Ayakala, Governor of Umma.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 26 (1974): 90–111.

Sharlach, Tonia M. “Šulgi-simti and the Representation of Women in Historical Sources.” In Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context. Studies in Honor of Irene J. Winter by Her Students, edited by Jack Cheng and Marian H. Feldman, 363–68. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2007.

Steinkeller, Piotr. “Seal Practice in the Ur III Period.” In Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, edited by McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs, 41–53. Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1977.

van der Toorn, Karel. Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel: Continuity and Change in the Forms of Religious Life. Leiden and New York: E. J. Brill, 1996.

van Koppen, Frans. “The Scribe of the Flood Story and His Circle.” In The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, 140–66. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Whiting, Robert M. “Tiš-atal of Nineveh and Babati, Uncle of Šu-Sin.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 28 (1976): 173–82.

Zettler, Richard L. “The Sargonic Royal Seal: A Consideraton of Sealing in Mesopotamia.” In Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, edited by McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs, 33–39. Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1977.

Endnote

1 Karel van der Toorn, Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel: Continuity and Change in the Forms of Religious Life (Leiden and New York: E. J. Brill, 1996), 66.

2 This impression was published by Dominique Charpin, Le clergé d’Ur au siècle d’Hammurabi (Geneva and Paris: Libraire Droz, 1986), 147.

3 Ibid., 147, 285.

4 For an edition of this text, see J. A. Brinkman, “The Western Asiatic Seals Found at Thebes in Greece: A Preliminary Edition of the Inscriptions,” Archiv für Orientforschung 28 (1981/82): 75.

5 For an edition of this text, see ibid.

6 van der Toorn, Family Religion in Babylonia, 66.

7 As noted by Dominique Charpin, “Les Divinités Familiales des Babyloniens d’après de leurs sceaux-cylindres,” in De la Babylonie à la Syrie en passant par Mari. Mélanges offerts à Monsieur J.-R. Kupper à l’occasion de son 70e anniversaire, ed. Ö. Tunca (Liège: University of Liège, 1990), 65–66.

8 As argued by van der Toorn, Family Religion in Babylonia, 66.

9 Piotr Michalowski, “The Mortal Kings of Ur: A Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia,” in Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond, ed. Nicole Brisch, Oriental Institute Seminars (Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 2008), 34.

10 Ibid., 35–40.

11 van der Toorn, Family Religion in Babylonia, 66–67.

12 This impression was published by Charpin, 49. It reads:

[Bal]munamh[e]

[Son of] Sîn-nur-ma[tim]

[Servant of Warad]- S[în]

13 YOS 12, 67 reads:

Balmu[nam]he

Scribe

Son of Sîn-nur-ma[tim]

Servant of Enk[i]

and […]

14 Richard L. Zettler, “The Sargonic Royal Seal: A Consideraton of Sealing in Mesopotamia,” in Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, ed. McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs, Bibliotheca Mesopotamica (Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1977), 31–38.

15 Ibid., 33–36.

16 Piotr Steinkeller, “Seal Practice in the Ur III Period,” in Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, ed. McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs, Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 6 (Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1977), 46.

17 As noted by P. A. Parr, “A Letter of Ur-Lisi, Governor of Umma,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 24 (1972): 135.

18 TCS 1, 190

19 TCS 1, 140

20 Drawings of the impressions of these seals were published by P.A. Parr, “Ninḫilia: Wife of Ayakala, Governor of Umma,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 26 (1974): 111.

21 Her earlier seal impression is known from its appearance on a tablet in the British Museum, BM 107558. Her later seal impression is used on various tablets, including HMA 9-02738, located in the Hearst Museum at the University of California, Berkeley.

22 Ibid., 93–99.

23 See Tonia M. Sharlach, “Šulgi-simti and the Representation of Women in Historical Sources,” in Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context. Studies in Honor of Irene J. Winter by Her Students, ed. Jack Cheng and Marian H. Feldman (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2007).

24 TCS 1, 215.

25 As suggested by Steinkeller, “Seal Practice,” 44.

26 Frans van Koppen, “The Scribe of the Flood Story and His Circle,” in The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 157–58.

27 Judith A. Franke, “Presentation Seals of the Ur III/ Isin-Larsa Period,” in Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, ed. McGuire Gibson and Robert D. Biggs (Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1977), 64–65.

28 TA 1931-T615

29 Robert M. Whiting, “Tiš-atal of Nineveh and Babati, Uncle of Šu-Sin,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 28 (1976): 178–79.