Late Bronze Age Cylinder Seals on the Island of Cyprus

The Late Bronze Age is a general designation for the time period from around 1600 to 1200 BCE across the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. It covers multiple cultures and geographic regions, including Minoan Crete, Mycenaean Greece, Hittite Anatolia (central Turkey), the Late Cypriot period on Cyprus, Middle Assyria in northern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), Kassite Babylonia in southern Mesopotamia, the city-states of the Levant (parts of southeastern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel), western Iran, and New Kingdom Egypt. The period is characterized by extensive exchange among these cultural regions, resulting in what has been called the first age of internationalism.1 These exchanges were complex and of varying types and degrees of intensity that included high-level diplomatic relations between state rulers, mercantile enterprise, the circulation of goods—both precious and commodities—and the interaction of artists and skilled practitioners. The internationalism of the period had an enormous effect on the development of the individual cultures over the course of the four centuries.

Cylinder seals during this period participate in and reflect the complex international and regional situations of the time. One indicator of international connections is the general spread of the cylinder seal shape beyond its traditional home of Mesopotamia. For example, cylinder seals appear on the island of Cyprus for the only time in its history, and they make a reappearance in the southern Levantine region after a hiatus of approximately one thousand years. Nonetheless, despite their small scale and portability, the vast majority of seals hew closely to regional styles and remain clustered in identifiable locales. Cyprus offers a particularly good window onto this Late Bronze Age world, which can be explored through the example of an interesting cylinder seal housed in the Freer Gallery of Art.

Cylinder seal. Hematite. Cyprus. Late Bronze Age, ca. 1600–1200 BCE. Freer Gallery of Art, F1999.6.42. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Leonard Gorelick.

Seal F1999.6.42 is carved out of hematite, one of the most popular stones for seal carving earlier in the second millennium and favored for high-quality seals on Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age (Figure 1). Its imagery shows a popular scene on the island, often referred to as the master or mistress of animals. A figure of uncertain gender in a long-skirted garment grasps in each hand the foreleg of two mythological beasts arranged to either side. To the left (the figure’s right) stands a sphinx, or human-headed, winged lion, while to the right a winged griffin mirrors the sphinx’s upright pose. All three figures wear double-banded belts. A secondary group on the seal depicts two lions seated on their haunches with their bodies crisscrossing one another and their forelegs held aloft. In the space below their bodies is a profile head, while a bucranium (bull’s head) hovers above. The two lions twist their heads in order to confront one another; the lion’s head to the left is slightly higher as if it were attacking the one on the right. The style of carving, along with motifs like the bucranium, identify this seal as a Cypriot creation.

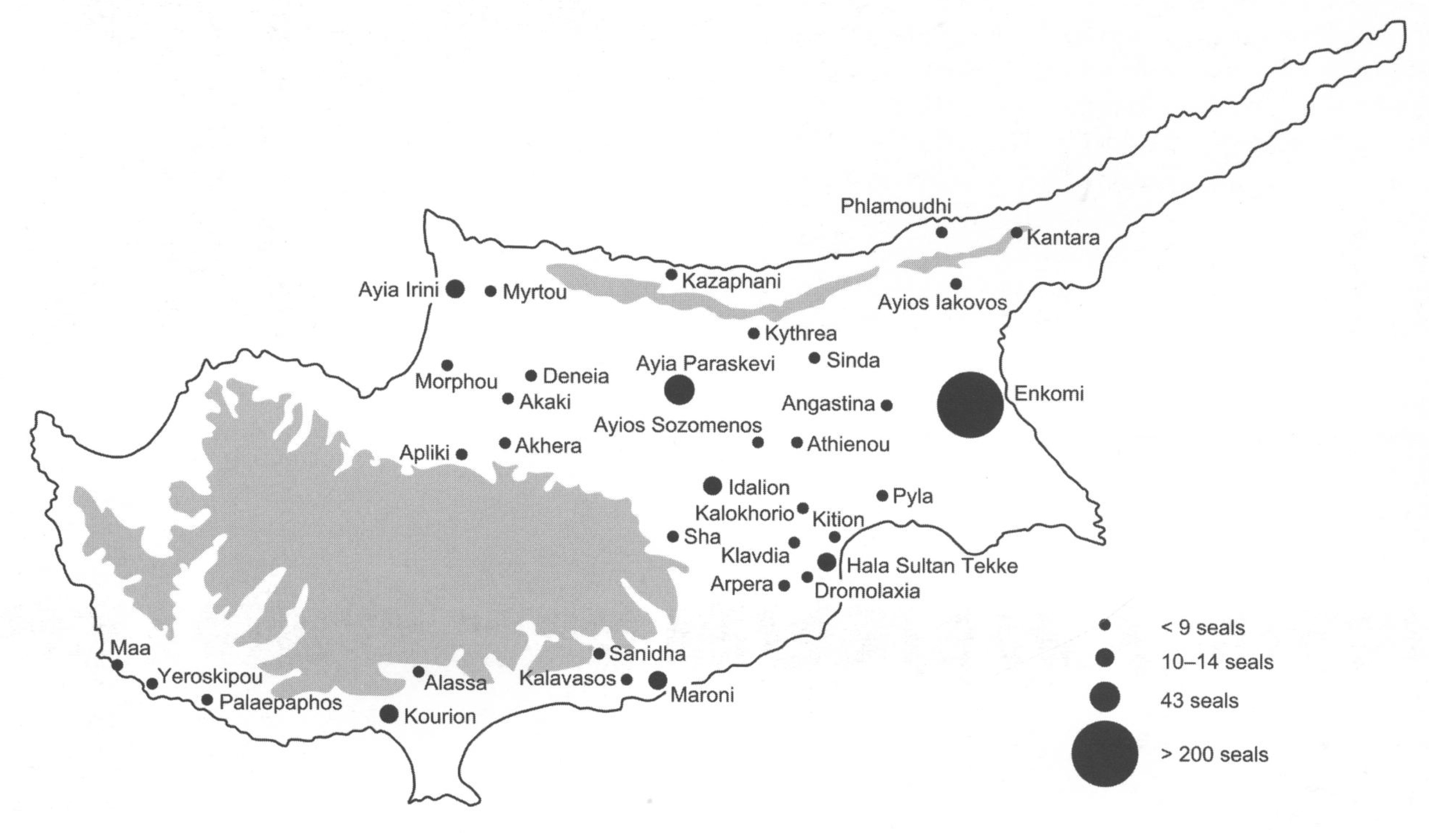

Imported examples of cylinder seals from Mesopotamia and Syria appeared on the island during the seventeenth century BCE.2 Around the end of the sixteenth or start of the fifteenth century BCE, cylinder seals began to be produced locally at sites around the island. Local production lasted through the thirteenth century but ceased with the collapse of the Bronze Age between 1200 and 1100 BCE, never to return.3 The largest number of local cylinder seals have been found at Enkomi on the eastern coast of the island, but they occur across Cyprus and exhibit a remarkable variety of stylistic and formal attributes (Figure 2).4 The distinct seal styles reveal a multiplicity of groups on the island at the time and suggest a decentralized political organization.5 This is in contrast with the limited textual evidence for political organization on the island, namely, a series of diplomatic letters sent from the ruler of an entity known as Alashiya. While the identification of Alashiya with part or all of Cyprus has been debated, petrographic analysis of the clay tablets sent from its ruler locate their origin on the island.6 It remains a question how to reconcile these two pictures of political organization, although it has been suggested among possible models that, while the island consisted of small, autonomous regional polities, these polities banded together behind a unified “leader” when engaging in international affairs.7

Cyprus: Distribution of provenanced cylinder seals. Jennifer M. Webb and Judith Weingarten, “Seals and Seal Use: Markers of Social, Political and Economic Transformations on Two Islands” (Parallel Lives: Ancient Island Societies in Crete and Cyprus), British School at Athens Studies 20 (2012): 88, Fig 6.2.

It is possible that the close connection between Enkomi and the Syrian trading kingdom of Ugarit on the mainland directly opposite laid the foundation for the adoption of the cylindrical form in Cyprus. Because clay sealings are almost entirely absent on the island, Cypriots do not appear to have taken over the administrative function of the sealing device, although seals themselves do occur in administrative contexts such as industrial and storage complexes.8 The largest number, however, have been excavated in burials where they served as items of adornment that signaled the prestige and status of the deceased. The appearance of the cylinder seal on Late Bronze Age Cyprus manifests a material and visual negotiation of power and status by the emerging elite classes at major urban centers such as Enkomi and Kition. Their access to foreign materials, such as hematite, and their use of exotic imagery drawn from motifs circulating in the Near East and Aegean, such as the sphinx and griffin, speak to Cyprus’s growing connectivity with the larger Mediterranean world.

Cylinder seal. Hematite. Syro-Mitannian. Late Bronze Age, ca. 1600–1200 BCE. Freer Gallery of Art, F1999.6.41. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Leonard Gorelick.

In 1948, Edith Porada defined thirteen different stylistic groups of seals that Jennifer Webb later divided into three main classifications: Elaborate (Porada’s Groups II–VI), Derivative (Porada’s Group VII), and Common (Porada’s Groups VIII–XII).9 Elaborate seals are characterized by hard stones, predominantly hematite, cut with highly modeled standing figures wearing detailed clothing and often associated with mythological animals. The Freer cylinder seal F1999.6.42 fits into the Elaborate group, with its detailed carved hematite depicting a figure between upright mythological beasts. The use of finely drilled rows of dots reoccurs in this group of seals, along with minute detailing seen, for example, in the creatures’ wings. Derivative seals depict similar subjects such as standing figures holding animals but in more simplified compositions with less detailing. The figures are usually shown in short tunics or pants and are depicted with long legs, narrow waists, full chests, stick arms, and small heads. The animals tend not to be mythological and often take a distinct S-shape position. Deep, rounded modeling is accentuated with wheel-cut striations and drilled dots. Derivative seals also tend to use softer stones such as chlorite. Common seals are characterized by scenes of a ritual or talismanic nature, such as seated figures with vegetation, vessels, or tables. These seals, which are also usually made of softer stones like chlorite, exhibit a variety of basic carving techniques, such as linear engraving, wheel-cutting, and drilling, with little or no evidence of secondary working. Another seal in the Freer collection, seal F1999.6.41, belongs to a related group of seals attributed to the mainland (Figure 3). These have been designated as Mitannian Common style, or—given that their distribution extends well beyond the borders of the political state known as Mitanni—as Syro-Mitannian.10 Like the Common style seals from Cyprus, they display an undisguised use of the drill, which is particularly evident in the eyes of the animals on the Freer example.

Cylinder seal showing a figure grasping an antelope by the tail, with a bucranium above an oxhide ingot to the side. Black-gray steatite. Late Cypriot, 16th–12th c. BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 74.51.4325. The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76.

As noted, the Late Bronze Age is the only time during which Cyprus produced seals in the cylinder format. This is also a time of significant political and cultural change for the island, as well as a time of unprecedented connectivity throughout the eastern Mediterranean. A central element propelling Cyprus onto the international scene is its newly emerging role as the main provider of copper. Although copper deposits were available on the island earlier, Cyprus only assumed the part of primary exporter during the Late Bronze Age. Copper, when alloyed with tin, produced the bronze for which the period from around 3000 to 1200 BCE is named.

Bronze statue of armed god standing on a base in the form of an oxhide ingot. From Enkomi, Sanctuary of the Ingot God. Cyprus Museum, Nicosia, Field no. 1142. Image by G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini Picture Library/Bridgeman Images.

Bibliography

Goren, Yuval, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Israel Finkelstein, and Nadav Na’aman. “The Location of Alashiya: New Evidence from Petrographic Investigation of Alashiyan Tablets from El-Amarna and Ugarit.” American Journal of Archaeology 107, no. 2 (2003): 233–55.

Goren, Yuval, Israel Finkelstein, and Nadav Na’aman. Inscribed in Clay: Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and Other Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, 2004.

Knapp, A. Bernard. Copper Production and Divine Protection: Archaeology, Ideology and Social Complexity on Bronze Age Cyprus. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology and Literature Pocket-book 42. Göteborg: P. Åström’s Förlag, 1986.

Knapp, A. Bernard. Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus: Identity, Insularity, and Connectivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Moran, William L. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Porada, Edith. “The Cylinder Seals of the Late Cypriote Bronze Age.” American Journal of Archaeology 52 (1948): 178–98.

Pulak, Cemal. “The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade.” In Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C., edited by Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, and Jean M. Evans, 289–305. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008.

Salje, Beate. Der ‘Common Style’ der Mitanni-Glyptik und die Glyptik der Levante und Zyperns in der Späten Bronzezeit. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern, 1990.

Smith, Joanna S. Seals for Sealing in the Late Cypriot Period. PhD thesis, Bryn Mawr College, 1994.

Van de Mieroop, Marc. The Eastern Mediterranean in the Age of Ramesses II. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007.

Webb, Jennifer M. “Cypriote Bronze Age Glyptic: Style, Function and Social Context.” In EIKON Aegean Bronze Age Iconography: Shaping a Methodology, edited by R. Laffineur and J. L. Crowley, 113–21. Liège: University of Liège, 1992.

Webb, Jennifer M., and Judith Weingarten. “Seals and Seal Use: Markers of Social, Political and Economic Transformations on Two Islands.” Parallel Lives: Ancient Island Societies in Crete and Cyprus. British School at Athens Studies 20 (2012): 85–104.

Endnote

1 Marc Van de Mieroop, The Eastern Mediterranean in the Age of Ramesses II (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007).

2 Jennifer M. Webb and Judith Weingarten, “Seals and Seal Use: Markers of Social, Political and Economic Transformations on Two Islands” (Parallel Lives: Ancient Island Societies in Crete and Cyprus), British School at Athens Studies 20 (2012): 88.

3 Stamp seals, which were produced prior to the Late Bronze Age, continued to be produced throughout the Late Bronze Age and subsequent Iron Age.

4 Webb and Weingarten, “Seals and Seal Use,” fig. 6.2.

5 Joanna S. Smith, Seals for Sealing in the Late Cypriot Period, PhD thesis, Bryn Mawr College, 1994; Bernard A. Knapp, Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus: Identity, Insularity, and Connectivity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 153.

6 Yuval Goren, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Israel Finkelstein, and Nadav Na’aman, “The Location of Alashiya: New Evidence from Petrographic Investigation of Alashiyan Tablets from El-Amarna and Ugarit,” American Journal of Archaeology 107, no. 2 (2003).

7 Yuval Goren, Israel Finkelstein, and Nadav Na’aman, Inscribed in Clay: Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and Other Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, 2004), 73–75.

8 Webb and Weingarten, “Seals and Seal Use,” 88.

9 Porada, Edith, “The Cylinder Seals of the Late Cypriote Bronze Age,” American Journal of Archaeology 52 (1948): 178–98; Jennifer M. Webb, “Cypriote Bronze Age Glyptic: Style, Function and Social Context,” in EIKON Aegean Bronze Age Iconography: Shaping a Methodology, eds. R. Laffineur and J. L. Crowley (Liège: University of Liège, 1992), 118.

10 Beate Salje, Der ‘Common Style’ der Mitanni-Glyptik und die Glyptik der Levante und Zyperns in der Späten Bronzezeit (Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern, 1990).

11 Cemal Pulak, “The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade,” in Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C., eds. Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, and Jean M. Evans, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 289–305; the image reproduced here is from Aruz, Benzel, and Evans, Beyond Babylon, p. 308, cat. no. 185a.

12 Pulak, “Uluburun Shipwreck,” 292.

13 William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 104–13.

14 Knapp, Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus.