Buddhist Art Patronage during the Goryeo Dynasty

Buddhist Art Patrons

As the national religion of the Goryeo 高麗 dynasty (918–1392), Buddhism spurred an active culture of religious projects on multiple levels of society. The so-called bulsa 佛事, or “Buddhist projects,” were collective undertakings sponsored by numerous patrons. These projects included establishing a new temple, enshrining Buddhist sculptures and paintings, and copying Buddhist scripture (sagyeong 寫經). Because a patron’s taste and resources tended to influence the material, contents, and standards of the work being sponsored, identifying the patron of any commissioned project is a critical component of art historical study. Inscriptions on paintings and votive texts from the interior cavities of sculptures often reveal important information about the sponsors. This data can be further analyzed with the help of other related records or historical material.[1] The present study examines notable sponsors of the Goryeo period, placing particular focus on those of the late Goryeo period.

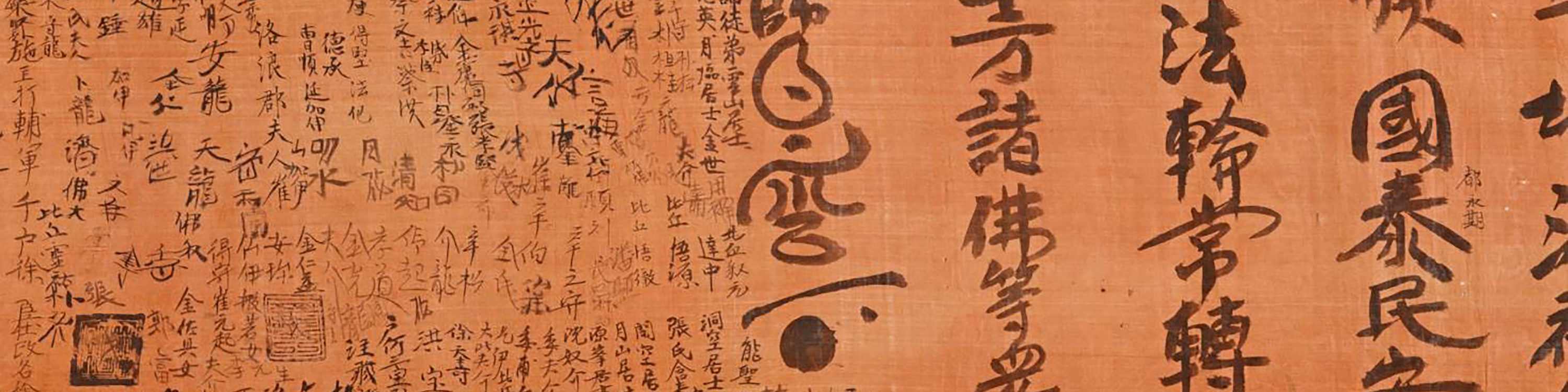

Sponsors of Buddhist art during this period were diverse. They included the royal family, nobles, pro-Yuan dynasty forces (buwon seryeokga 附元勢力家), Buddhist monks, Confucian literati, and commoners. From this list, one notable group of sponsors is members of the royal family, including the kings and queens. During the late Goryeo period, this group also included some members of the Yuan 元 imperial court. The main concern of this high-level group was the individual’s and family’s welfare, both in their current and future lives. They also prayed for peace and stability for the kingdom or empire and its people. King Chungseon 忠宣 (r. 1298, 1308–13) was an exemplary royal sponsor. He actively engaged monks of various sects and sponsored Buddhist projects on a large scale. The conversion of a royal palace to Mincheonsa 旻天寺 under his auspices and his commissioning of some three-thousand sculptures are among his famous achievements. In 1310, one of his consorts, née Kim (Sukbi Kim-ssi 淑妃金氏), sponsored a painting of the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara, now in the collection of Kagami-jinja 鏡神社, Japan. Other kings and queens sponsored art of historical importance. In 1346, a copper bell for Yeonboksa 演福寺 was cast to commemorate Goryeo King Chungmok’s 忠穆 (r. 1344–48) and Princess Deoknyeong’s 德寧 public supplication. Made by Yuan craftsmen, the bell now hangs at the South Gate of Gaeseong 開城, North Korea. Finally, before being crowned, Yi Seong-gye 李成桂 (1335–1408), a nobleman and founder of the Joseon 朝鮮 dynasty (1392–1910), carried out a Buddhist service when he sponsored the enshrinement of a sarira reliquary on Birobong Peak 飛盧峯 (Fig. 1), which is the highest point of the Diamond Mountain (Mt. Geumgang 金剛山) range. This Buddhist service was Yi’s attempt to secure the Buddha’s support for his political designs. Yi Seong-gye’s name also appears in the dedication text for a silver Amitabha triad of 1383, now in the collection of the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

The Birobong Peak reliquary is a significant example of a royal Buddhist project, as it was dedicated by the future king and included his family. It consists of multiple components, including a glass ritual reliquary, a sliver-plated sarira tower, and a silver-plated octagonal sarira reliquary, all enclosed in an outer case. In addition, the Leeum Amitabha triad was made in 1383 when Yi Seong-gye was still serving as the Commander of the Northeastern Township (Dongbuk myeon doji hwisa 東北面都指揮使). This was also when Jeong Do-jeon 鄭道傳 (1342–1398), who would become Prime Minister of the Joseon dynasty, paid his historical visit to his future king. Notably, Yi’s name appears on the dedication for the triad without any title.[2]

Sponsorship of Buddhist art also became popular among the nobility in the form of small-scale temples, sculptures, paintings, or copied scripture. While “Buddhist projects” were originally conceived for ritualistic purposes, in practice these undertakings allowed donors to express well-wishes for the emperor and the king, as well as to secure one’s family pedigree and prosperity in their present and future lifetimes. In times of foreign invasion, some of the inscriptions pleaded for the enemy’s retreat. Among the famous Goryeo project patrons whose dedications fall under this category are Jo In-gyu 趙仁規 (1237–1308), who renovated Cheonggyesa 淸溪寺, a royal retainer Yeom Seung-ik 廉承益 (?–1302), who offered his house as a place for copying scriptures (geumja daejang sagyeongso 金字大藏寫經所), a high-ranking official Kwon Bok-su 權福壽 (1262–1346), who sponsored the production of the painting Buddha Amitabha in the collection of the Nezu Museum, Tokyo, and a general Choi Yeong 崔瑩 (1316–1388), who sponsored the repair of the pagoda from Anyangsa 安養寺 in Geumju 衿州. Ko Yongbong 高龍鳳 and Kang Yung 姜融, pro-Yuan power holders, can also be counted among the late Goryeo sponsors for whom family prosperity was the primary objective. Together, the Ko 高 and Kang 姜 families commissioned a ten-story stone pagoda (13.5 meters tall) at Gyeongcheonsa 敬天寺 in March 1348.

One noteworthy aspect of Goryeo Buddhism is the active participation of female patrons, mainly consisting of the “Dame(s) of the County” and Buddhist nuns. “Dame of the County (Gunbuin 郡夫人)” was a title for women whose sons or husbands held high-ranking offices. Each dame’s title would be completed by adding the name of a region associated with her husband or son. For example, on the votive inscription for a gilt-bronze seated Medicine Buddha (Yaksa yeorae 藥師如來, Skt. Bhaishajyaguru) at the Janggoksa 長谷寺 are twenty-eight names titled “Dames of (X) County,” including Yi Eon-chung’s 李彦冲 (1273–1338) wife “Dame of Gangnyeong County 江寧郡夫人, née Hong 洪,” and Choe An-do’s 崔安道 (1294–1340) wife “Dame of Bakneung County 博陵郡君夫人, née Gu 具.” Choe and his wife are also the patrons who commissioned the illustrated thirty-first fascicle of the Flower Garland sutra, now in the collection of the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art. This practice reveals an aspect of Goryeo period social structure which tightly linked a woman to the socio-economic status of her husband or son.

Nuns also emerged as a prominent group of female supporters for religious projects. At the Garden of Pure Occupation (Jeongeop-won 淨業院), or the Garden of Peaceful Retreat (Anil-won 安逸院), which is believed to have been a nunnery in the Goreyo capitol Gaegyeong 開京, a nun named Myodeok 妙德 actively participated in various Buddhist projects. One such project was the publication of the Concise Verse on Pointing Directly to the Heart (Jikji shimche yojeol 直指心體要節), which was printed in 1372 using movable metal type. Such active participation from female clergy is a characteristic of Buddhist art as a genre.

However, monks were just as active in their patronage. Among the most famous projects sponsored by monks are the painting of the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara, dedicated by the monk Yukjeong 六精, now in the Sumitomo Collection, and the painting of the Sixteen Meditations of Sukhavati (from the Visualization Sutra) in Chion-in 知恩院 in Kyoto. The latter was dedicated in 1323 by six monks, including one who was both the Director of the Clergy at Jeongup-won (a nunnery for the women of the royal family) and the Great Master of Meditation (Daeseonsa 大禪師), the highest-ranking master in Seon 禪 (Ch. Chan, Jp. Zen) Buddhism. In addition, clergy-sponsored sculptural projects tended to involve larger groups of supporters, often revealing sectarian leanings and group interests.

Buddhist projects by scholar-officials trained in Confucian classics were yet another unique feature of this period. While firmly grounded in neo-Confucianism, the scholar-officials continued to forge strong ties with Buddhist monks and offered them support. Their Buddhist projects were often conducted in honor of rulers and parents, rather than as an expression of personal faith. It could be said that Buddhism offered these scholars a means by which to practice Confucian piety.

Sponsors involved with the deposit of dedication materials

One of the best ways to understand Goryeo sponsors of Buddhist projects is to examine the practice of depositing sacred objects or dedication material (bokjangmul 腹藏物, lit. [sacred] innards). The term “bokjangmul” refers to various objects that are inserted into a carved cavity of a sculpture. This act reveals a desire to animate and empower man-made icons, as well as a strong preoccupation with wish-fulfillment in Buddhism.

Though made by human hand, Buddhist sculptures and paintings were believed to come alive through the process of an “eye-opening ceremony (jeoman 點眼)” (ceremonial painting-in of the pupils of an icon) and by depositing the “hidden treasures” inside a sculpture. Inserting the objects thus developed as an important Buddhist ritual.[3]

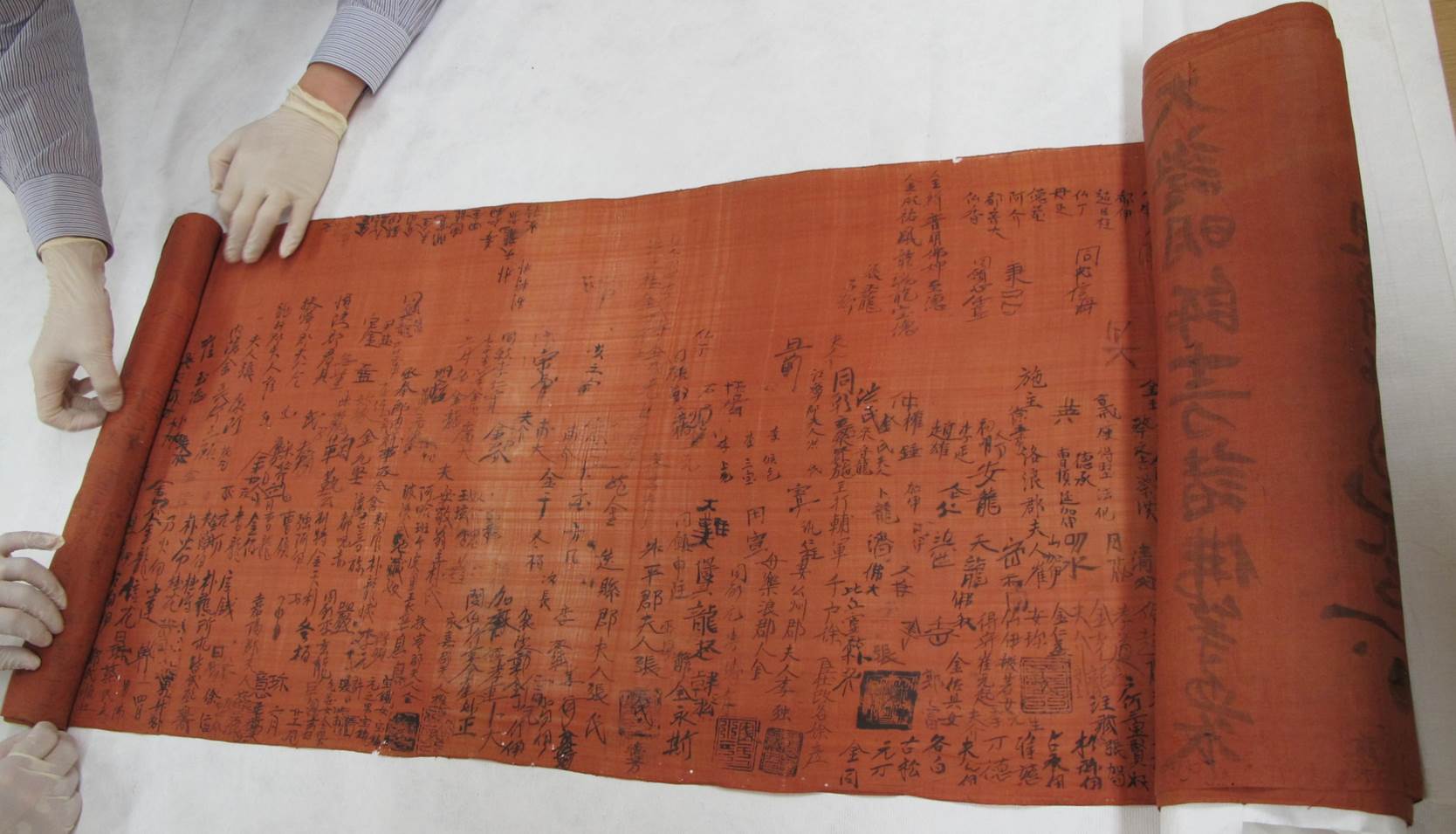

Dedication materials thus far discovered include votive inscriptions, Buddhist scriptures, dharanis (esoteric Buddhist incantations), cylindrical containers called “throat-bell containers” (huryeongtong 喉鈴筒), textiles, and costumes. These hidden treasures were deposited both as material fillers and, as the name suggests, sacred objects, embodying the Buddhist ideals and doctrines current at the time. The practice continued to develop as it incorporated ritual regulations as specified in the scripture, while it also built upon the cosmological principle of the Five Directions (obang 五方). This convergence of traditional Buddhist ritual regulations and Daoist cosmology would ultimately result in the publication of the Sutras on the Production of Buddhist Images (Josang gyeong 造像經) during the Joseon dynasty.

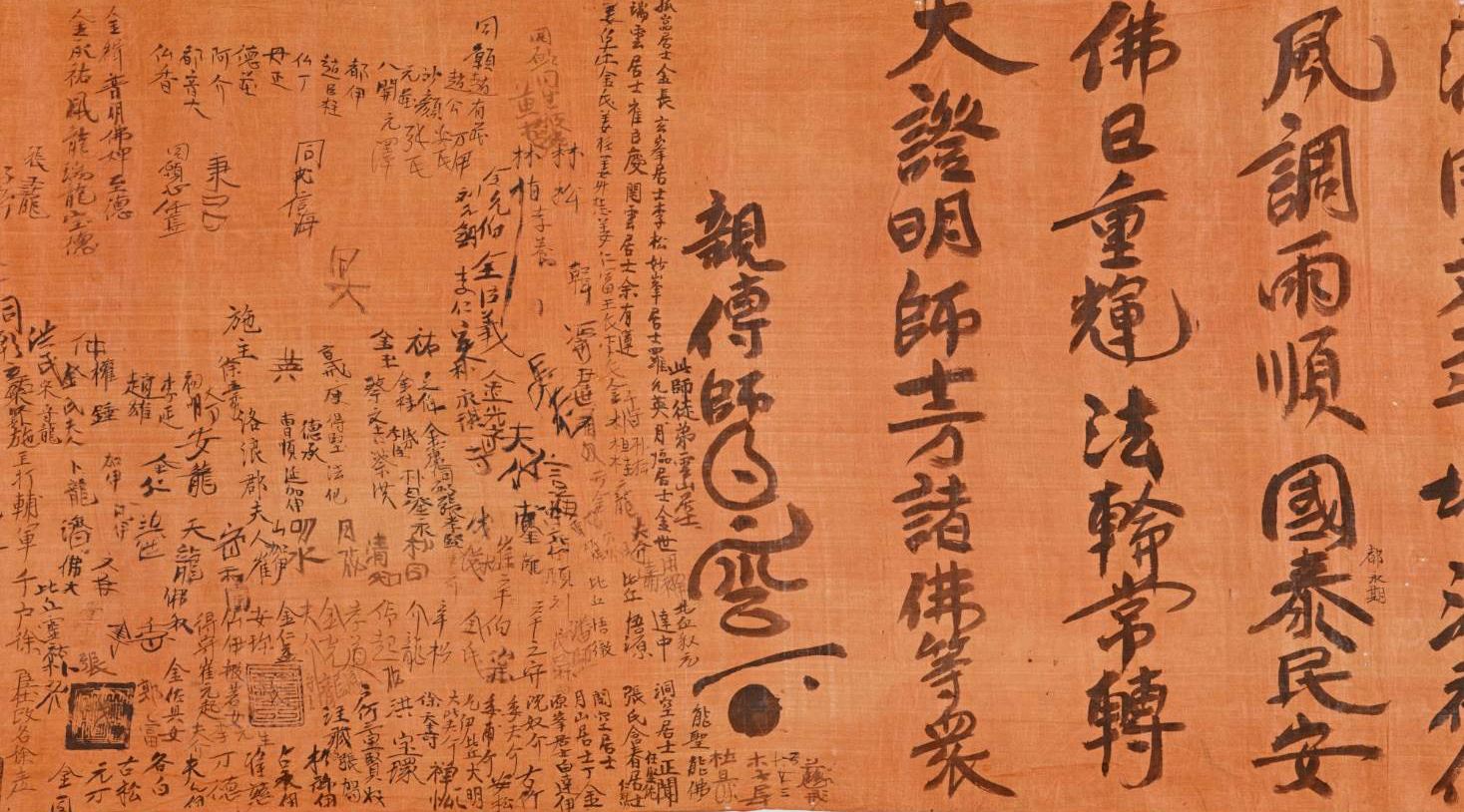

The demographics of patronage tend to vary depending on the period, location, and purpose of production. It is possible to analyze the correlation by examining works that include votive inscriptions among the dedication materials. The votive inscriptions found in the cavities of Buddhist sculptures are valuable because they shed light on their sponsors, as well as on the date, location, and purpose of the production. There are about fifteen Buddhist sculptures with sacred objects. A total of six votive inscriptions are known to exist of which three relate to sponsored repairs. They are made of various materials, including silk and paper of a wide range of sizes (from 20-30 centimeters to 10 meters on one side). The format of these inscriptions also varies. Some contain a single dedication with one name, while others carry a dedication by one representative, whose name is listed among those of a larger group of donors. Typically, the remaining patrons wrote their own names. Some, however, used chops or seals to leave an impression, and some relied on a surrogate scribe—possibly because their names involved difficult Chinese characters. Other notable names were those that used the Idu 吏讀 system, an early Korean writing method that utilized Chinese characters to represent “pure Korean” phonetic values. For example, Chinese characters 石金 were used to represent the Korean name Dol-swe, as “dol” means stone and “swe” means metal in Korean.

Heading each votive inscription is a title that encapsulates the express purpose of the sponsored project. Typical examples include: “Votive Text upon the Creation of an Image of the Thousand-Arm Avalokiteshvara (Cheonsu gwaneum juseong wonmun 千手觀音鑄成願文),” “Text in Dedication of the Image of Avalokiteshvara to Whom We Aspire to Form a Tie (Gwaneum juseong gyeoryeonmun 觀音鑄成結緣文,” “Jeon In-hyeok’s Votive Text (Jeon In-hyeok barwonmun 田仁赫發願文),” “Votive Text to be Deposited in the [Image of the] Buddha Amitabha (Mita bokjang barwonmun 彌陀腹藏發願文),” “Prayer in Hopes of Becoming a Buddha (Seongbul wonmun 成佛願文),” and “Votive Text in Unison, from the Daedeok Period (1297–1307) (Daedeok dong barwonmun 大德同發願文).”

The most important aspect of the inscriptions is the fact that every sponsor’s name is registered, thus helping us better understand Goryeo period patronage, as well as the modes and scale of sponsorship. During the Goryeo dynasty, it was common for the names on the votive texts to appear without any social titles, obscuring any social gaps among the listed sponsors. It is, however, possible to discern the number of sponsors involved in each project. There are, for example, a Thousand-arm Avalokiteshvara that was sponsored by 307 devotees, a Seated Buddha Amitabha image in Munsusa 文殊寺 sponsored by 214 donors, a Buddha image at Janggoksa 長谷寺 supported by 1,078 individuals, and the silver Amitabha Buddha triad at Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art sponsored by 273 people. All of these examples suggest that the support of religious associations made these costly sculptural projects possible. A gilt-bronze Avalokiteshvara at Buseoksa 浮石寺 on West Mountain (Seosan 西山), donated by 32 patrons, is a rarer example of a sculptural project supported by a smaller group of patrons.

One of the projects sponsored by the largest number of donors was the making of the aforementioned Buddha image at the Janggoksa in 1346. The project was spearheaded by Monk Baegun 白雲, who was the editor for the Scripture on Pointing Directly to the Heart (Jikji sim gyeong 直指心經), which remains the world’s oldest extant book printed using movable type. For this project, male supporters significantly outnumbered their female counterparts. Nevertheless, the donor group as a whole shows remarkable diversity. It includes public officials such as Nangjang 郎將 (a position in the fifth rank), Byeoljang 別將 (assistant military managers), and Pangwan 判官 (civilian officers), as well as commoners who do not possess surnames and persons of yet lower classes. There are even donors with Mongol names.

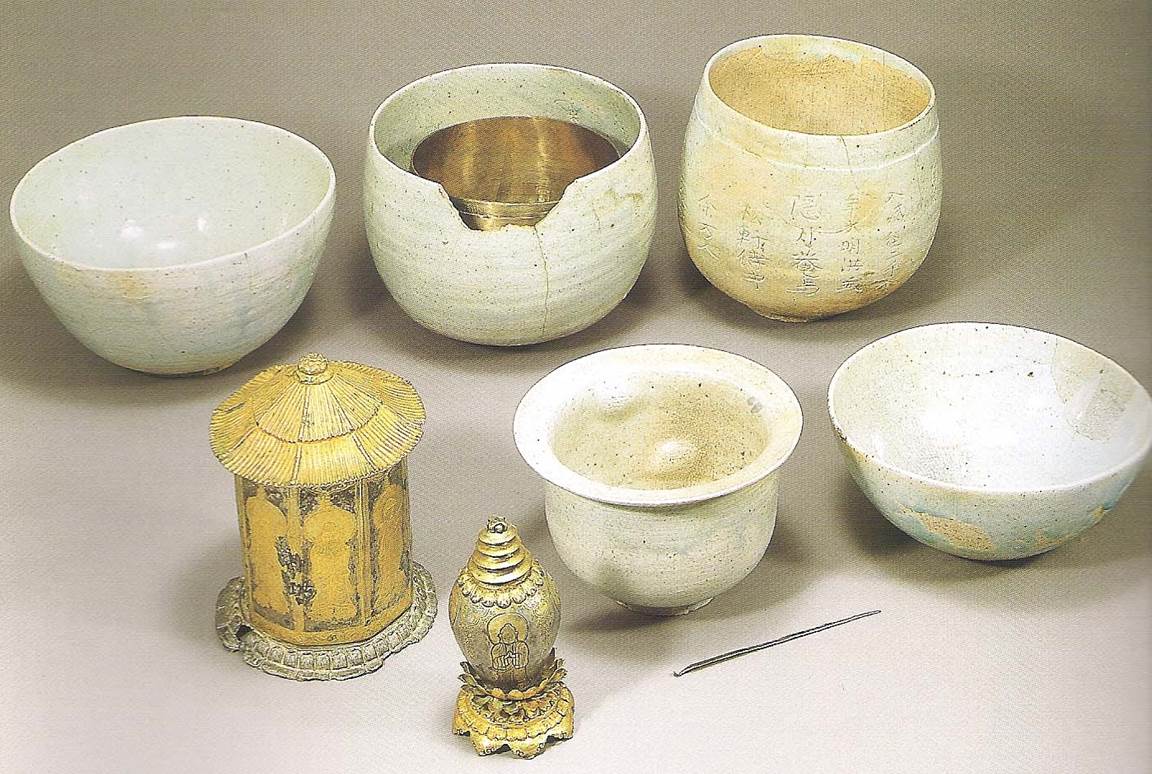

On average, the gender division among an upper-class donor group has men in the majority, often exceeding seventy percent. The group that paid for the aforementioned Thousand-arm Avalokiteshvara has a division of 61.7 percent male to 38.3 percent female. In the cases of the Janggoksa image, the seated Amitabha of Munsusa, and the silver Amitabha triad of the Leeum collection (Fig. 2), male donors represent 80.4, 83.9, and 86 percent, respectively, of the upper-class patrons for each project.

Male donors (across the range of social classes) average seventy to eighty percent of listed donors. But when there are relatively fewer upper class lay donors, we tend to see a significant number of male clergy among the patrons. For reference, the standard method of dividing listed donor names into “upper” and “lower” classes of the Goryeo period is by considering “upper-class” all males whose names include a surname (generally local functionaries and above) and females who are identified with surnames of their father’s families. All others—except the clergy—are relegated to the “lower class.”

Sponsors may list all items being offered. Sometimes they specify a purpose for making their offerings. Examples of the former from the Gaewunsa 開運寺 are a line professing that “having sold a beloved horse, I purchased the gold to be used for gilding [the image],” and another that reads “I offer one roll of hemp cloth needed for the renovation of the Buddha image.” In texts that indicate the purposes behind donation, predominant themes include passage into eternity, being reborn in paradise, being spared from illnesses, and the enjoyment of longevity in this life. One interesting inscription is a wish for the long life of a two-year-old baby. Self-cultivation, enlightenment, and a vow to aid sentient beings after one achieves enlightenment comprise the main thrust of many texts, as do the wishes for a living family member’s health and longevity, and a deceased family member’s safe arrival in paradise.

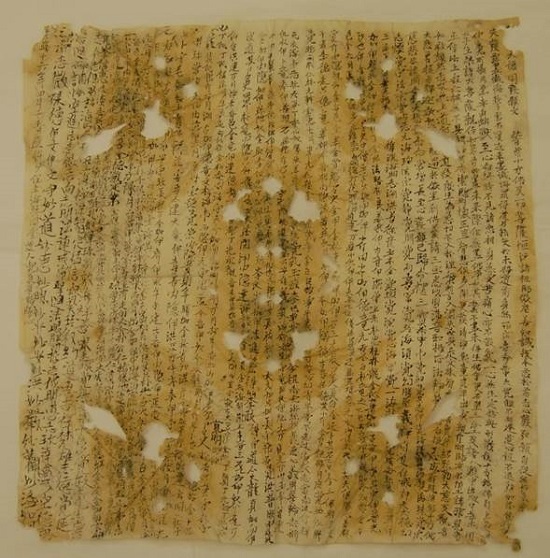

A votive inscription from 1302 on a work now in the collection of the Onyang Folk Museum includes a supplication by the family of Kim Banggyeong 金方慶 (1212–1300) of the Kim clan of Andong 安東 province, which was at the time a Kim lineage of the highest pedigree. The prayer includes a line from the Original Vows of the Medicine-Master Tathagata of Lapis Light (Yaksa yeorae bonwon gongdeok gyeong 藥師如來本願經), which expresses a woman’s desire to be reborn as a man in a future life (Fig. 3). The wish to be reborn a man is also found in the “Chapter on the Vows of Samantabhadra” in the forty-volume version of the Flower Garland sutra, as it is one of the “Forty-eight Vows of Buddha Amitabha.”

Another supplication of interest is one that vows to be reborn as a boy to a Chinese household of correct Buddhist faith, so that later he might leave home to become a monk rather than seek the prestige of rulership or high office. This unusual content can be explained by considering the date of the production of the image. For Goryeo, the year 1302—the twenty-eighth year of King Chungnyeol’s 忠烈 second reign period (r. 1274–98, 1299–1308)—marks a point of strong interference from, and a period of active sociopolitical engagement with, the Yuan dynasty. The desire to be associated with the stronger sovereignty might be attributed to these circumstances.

Wishes for a deceased family member’s rebirth in a Buddhist paradise also emerged prominently at this time. Names of deceased souls, including those of a departed mother, wife, or sister, were often included in the list of sponsors. This was a means by which to help the departed souls accrue more karmic merit, so that they could be reborn in Buddhist paradise and ultimately attain enlightenment.

Another noteworthy feature of the late Goryeo culture of votive writing was the inclusion of everyone in a household, including house slaves, as a collective unit dedicating a Buddhist project. The text found in the cavity of the gilt-bronze Amitabha of Munsusa, titled “Votive Inscription for Dedication, Upon the Casting of the Amitabha Image (Juseong Mita bokjang iban barwonmun 鑄成彌陀腹藏入安發願文),” lists parents, maternal and paternal aunts, brothers and sisters, cousins, and servants and their families, presenting everyone as supplicants. The text from the Janggoksa image also reveals a mother who prays for the health and welfare of her family members.

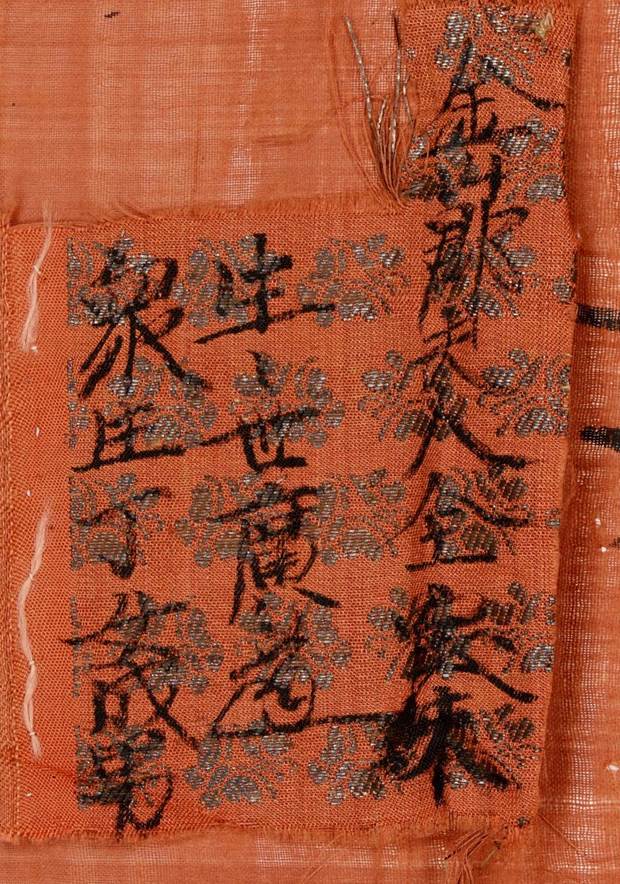

Yet another notable feature of votive inscriptions from the late Goryeo period is the appearance of Mongolized names. Goryeo names converted into the Mongol-style, such as Dorugy—represented by various Chinese characters (都兒赤 or 朶兒赤), including Kim Dorugy 金朶兒只—are found in documents from this period. Perhaps the most fascinating among this category of texts is the inscription that was found in the seated gilt-bronze Medicine Buddha of Janggoksa (Figs. 4 and 5), which reads “Longevity for the great Yuan (Daewon 大元) Bayan Temur 伯顔帖木兒.” Written in a small script in the upper portion of the text, the name Bayan Temur was the Mongol name given to Wang Gi 王祺 (1330–1374), who was the brother of King Chunghye 忠惠 (r. 1330–32, 1339–44) and would later succeed to the throne as King Gongmin 恭愍 (r. 1351–1374). Born in the seventeenth year (1330) of his father King Chungsuk’s 忠肅 reign (r. 1313–30, 1332–39), Wang Gi traveled to the Yuan court in 1341 on the Yuan emperor’s wishes. Thus, the inscription found in the Janggoksa Medicine Buddha is believed to carry a wish for King Gongmin’s longevity.

Conclusion

Buddhist art from the Goryeo period accompanied by written documentation, or works that are preserved entirely intact, are few in number. By analyzing these few existing works, it becomes clear that patrons from diverse social groups, including the royal court, supported Buddhist art in the Goryeo period and that the patrons’ choices largely determined the subject and quality of the sponsored projects. Since its material and content varied according to the sponsor, the sponsors and their votive inscriptions are important in helping us understand their wishes and the purpose of the art.

Notes

[1] Jeong Eun-u (Jeong Eunwoo) 鄭恩雨, “Goryeo hugi bulgyo misul ui huwonja 고려후기 불교미술의 후원자,” in Goryeo hugi bulgyo jogak yeongu 高麗後期 佛敎彫刻 硏究 (Seoul: Munye chulpansa 2007), 15–52.

[2] Jeong Eun-u (Jeong Eunwoo) 정은우, “1383-nyeon myeong eunje Amita yeorae samjon jwasang barwonmun ui geomto wa uiui 1383년명 은제아미타여래삼존좌상 발원문의 검토와 의의 [Review and Significance about Record of Silver Amitabha Triad Buddha Statue in 1383 Inscription],” Ihwa sahak yeongu 梨花史學硏究 43 (2011): 165–94.

[3] Jeong Eun-u (Jeong Eunwoo) 정은우, “Goryeo sidae bulbokjang ui teukjing gwa hyeongseong baegyeong 고려시대 불복장의 특징과 형성배경 [Characteristics and Formative Backgrounds of Sacred Objects Stored in Buddhist Images of the Goryeo Period],” Misulsahak yeongu 美術史學硏究 286 (2015): 31–58.

Bibliography

Jeong eun-u 정은우 and Sin Eun-je 신은제. Goryeo ui seongmul, bulbokjang 고려의 성물, 불복장. Gyeonggido Paju: Gyeongin munhwasa, 2017.

Jeong eun-u (Jeong Eunwoo) 정은우. “Goryeo sidae bulbokjang ui teukjing gwa hyeongseong baegyeong 고려시대 불복장의 특징과 형성배경 [Characteristics and Formative Backgrounds of Sacred Objects Stored in Buddhist Images of the Goryeo Period].” Misulsahak yeongu 美術史學硏究286 (2015): 31–58.

Jeong eun-u (Jeong Eunwoo) 정은우. “1383-nyeon myeong eunje Amita yeorae samjon jwasang barwonmun ui geomto wa uiui 1383년명 은제아미타여래삼존좌상 발원문의 검토와 의의 [Review and Significance about Record of Silver Amitabha Triad Buddha Statue in 1383 Inscription].”Ihwa sahak yeongu 梨花史學硏究 43 (2011): 165–194.

Jeong eun-u 鄭恩雨. “Goryeo hugi bulgyo misul ui huwonja 고려후기 불교미술의 후원자.” In Goryeo hugi bulgyo jogak yeongu 高麗後期 佛敎彫刻 硏究, 15–52. Seoul: Munye chulpansa, 2007.