Milly Finch, by Alba Campo Rosillo

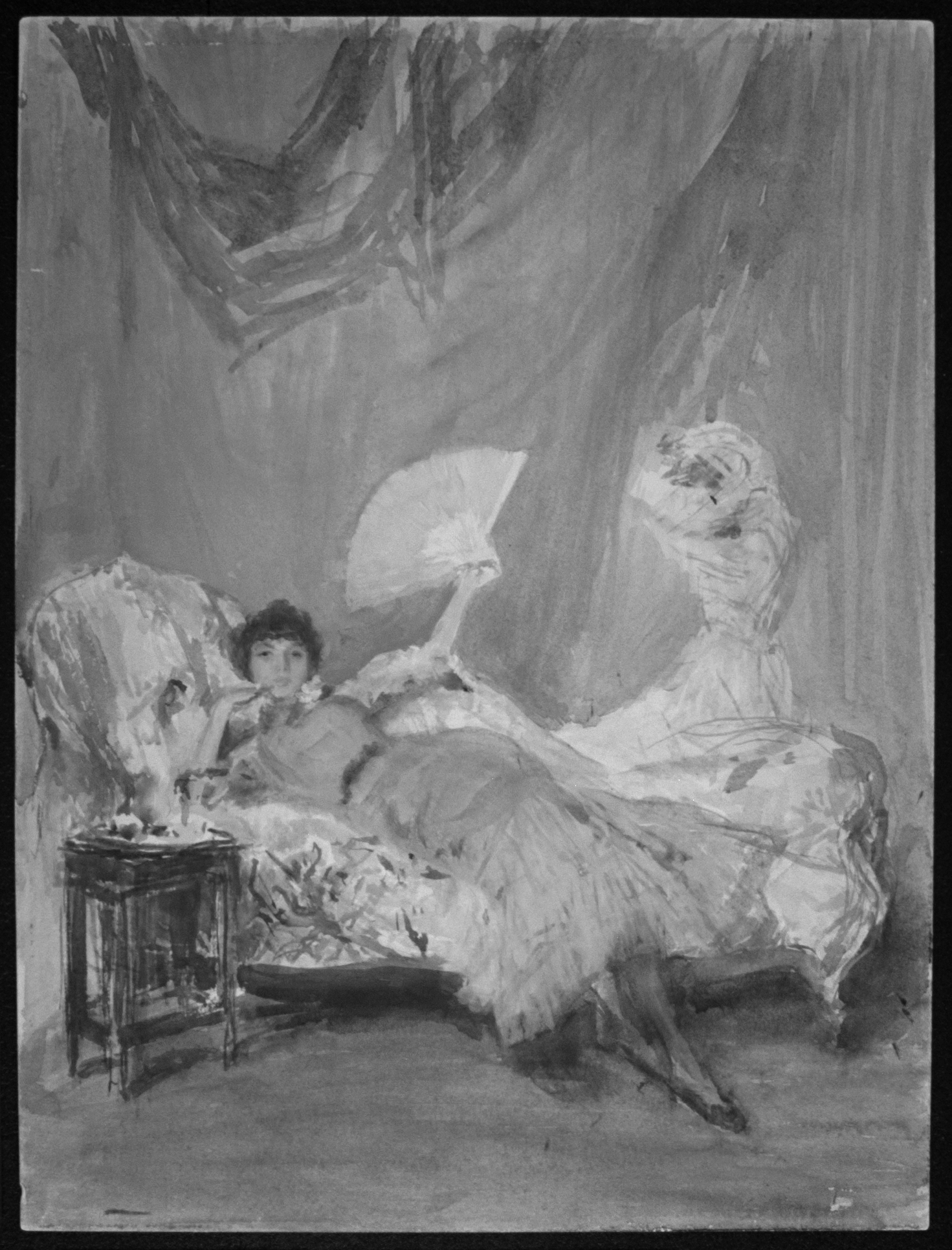

The watercolor Milly Finch signifies a turning point in James McNeill Whistler’s career. Created from 1883 to 1884, the painting constituted an intriguing study of ruptures and continuities, revealing the changing affiliations in Whistler’s personal, professional, and aesthetic fields. The circumstance of its creation prior to the presentation of the “Ten O’Clock” lecture in 1885 makes it a visual attack on everything his lecture would verbally confirm, reinforcing the idea that he cherished provocation in his life and work. The painting depicts Milly Finch reclining seductively on a chaise longue in an indoor setting. Finch was a professional model who posed often for Whistler during the 1880s when Maud Franklin, his model and mistress, was ill. She is holding open a coral red folding fan with her left hand and touches her lip with her right little finger. Next to her, there is a small table with an elongated artifact on top. A second female figure, likely Maud Franklin, is dressed in pink and sits behind Finch. This second figure is likely tying the knot of the foulard behind her neck. In the background, blue and purplish-gray drapery cascades on a studio backdrop.

The composition has a playful character due to its combination of multiple techniques. Although there is not an overall wash, gray washes appear in localized areas, such as in Finch’s dress and on some sections of the sofa. The background has been built using broad brushstrokes of watered-down lilac color next to a section painted in dusky rose applied with thin, elongated strokes behind Franklin on the right. Whistler contoured the two women’s profiles and the chaise in black using the brush as a pen. Finch’s dress is painted with mauve-colored strokes spread out over a previous layer of gray and a darker shade of purple. Franklin has been lightly painted with thin, translucent strokes that allow the black lines to show through, helping emphasize the body’s pose. The original cream color of the wove paper can be seen throughout her figure. Contrastingly, Finch’s coral fan and the mauve-colored, lower ruffles of her dress are painted with opaque, pastel-like strokes that open up from a central point where her legs are crossed, which suggests an inverse rendering of the fan’s triangular shape. Infrared photography (Fig. 1) reveals that Whistler painted over these two sections of the painting to reduce the size of the fan (which originally reached Finch’s head) and the width of the dress (which extended on both sides), making the fan and the dress look “small and dainty”—a description he applied to the watercolors themselves in an attempt to market them as easily portable to American tourists in London.1 Semitransparent strokes of vermillion partially cover the surface of the chaise, revealing touches of black, beige, and light coral that were previously applied. Mauve-colored strokes are spread out on top of the vermillion as well, suggesting a floral pattern on the chaise’s fabric. Purely gestural strokes come out of the right corner of the chaise, like a lobster’s antennae, echoing the electrified blue lines juxtaposed on the gray lilac in the background. In comparison to the undulating strokes Whistler uses to create the chaise’s floral pattern and its movement, the little brown table next to Finch appears static as a result of the dry, wiry application of pigment. Echoing the tension between lilac and red on Milly’s dress set against the chaise and fan, Whistler painted his colophon signature with controlled strokes in red above the blue, wiry drapery in the background, evoking a delicate butterfly haphazardly positioned on a spiky tree branch. The drama that the clashing nature of colors and lines produce recreates an atmosphere of controlled danger and excitement.

From the contrasting color and paint application in Milly Finch, Whistler produced a work that is visually captivating. The red, undulating areas and more static, spiky strokes of the table give the composition a charged energy that is counterbalanced by the presence of the soothing pale washes of purple in the background. The contemporaneous compositions Red and Pink–La Petite Mephisto (Fig. 3) and Note En Rouge–L' Éventail (Fig. 4), both from 1884, similarly experiment with red color, and they suggest not only Whistler’s investment in red at the time but also his willingness to use it for provocation. In a review of several works exhibited in 1884, Frederick Wedmore defined Le Petite Mephisto as “triumphant boldness and dash.”2 Given that many red and purple paints were new industrial colors, and quickly became “suspect” colors associated with “primitive” and lower class taste, the chromatic choice might have looked gaudy and refined at the same time to match what Margaret Macdonald calls the “mixture of elegance and rakishness” of the artist’s own appearance.3 Whistler’s style challenged not only good taste, but the principles of an Aestheticism seeking to visualize and express highly idealized beauty as anathema to the industrial, garish products transforming the look and feel of everyday life. The Aestheticism that Whistler rejected originated in Pre-Raphaelitism and was linked to the Arts and Crafts movement, which drew inspiration from paintings of the Gothic and Renaissance periods. In his “Ten O’Clock” lecture, Whistler denounced the “false prophets” who misunderstood art as ethics or as fashion, directly attacking art critics John Ruskin, Harry Quilter, and Sidney Colvin for the former and Oscar Wilde for the latter.4 The attack was amplified in the painting with the application of both red and mauve-colored paint on Finch’s face as make-up, emphasizing her transgressive and emancipated character as one of the “New Women” Whistler painted in the 1880s.5 To temper the backlash, he endeavored to tame the chromatic provocation of industrially made and industrially looking colors by harmonizing all the shades (industrial and traditional) in the work with bone black and zinc white (visible as yellow fluorescent passages in the ultraviolet image) (Fig. 2).6 This was in agreement with his idea that art was in constant change and that the artist should be able to draw inspiration from different periods but not be hostage to any of them.7 Whistler’s watercolor was a bid for artistic freedom and modern life.

The affront to the Aesthetic palette corresponds in attitude to the provocative and sexually suggestive pose assumed by Milly Finch. Opposed to the feminine ideal of a nude and sleeping Venus, or the languid-looking women pictured within contemporary masterpieces of the Aesthetic movement, Finch stares defiantly at the viewer while gesturing to her full red lips in an overtly erotic invitation. Building upon the reclining woman series that Édouard Manet painted in the 1860s and early 1870s (Fig. 5), Whistler suggests Finch’s sexual desire through her open fan and flaring skirt.8 Her eroticism surrounds her like a halo as accents of the same red pigment appear on her lips, stockings, and fan, constituting a triangle of arousal. In contrast to Finch’s bold presence, Maud Franklin appears as a ghostly figure fading from the visual field and, soon enough, from Whistler’s life. Finch emerges in this work as a kind of interloper in Whistler and Maud’s relationship, perhaps provoking his sexual interest in other women and pointing toward his loss of interest in Maud, which was confirmed in 1888 when Whistler married Beatrice Godwin. Contemporary images show Maud much more reserved and distant, an attitude probably due to her convalescence from several pregnancies. It is both the undulating shape and gestural strokes of the chaise that even suggest the somatic interaction of the artist with Finch’s body. The tension between the vitality of Finch and the dullness of Franklin suggests Whistler was moving onto something new. Indeed, the contours of Franklin’s ghostly head and the peak of her hair fringe have been captured in two different positions, which reveals Whistler’s fascination for contemporary developments in photography that could capture the visual effects appearing as specters of bodies in motion.9 Whistler’s use of visual technologies, such as watercolor paint and photography, obeyed as much a creative gesture as an urge to express emotional states.

Several aspects of the work speak to Whistler’s fluid depiction of reality. Milly Finch is wearing an Aesthetic dress, characterized by its lack of corset, loosely flowing fabric, and natural waist.10 The pulled flounced skirt reveals red stockings—a bold choice common among progressive women at the time—which Whistler also captures in Note in Pink and Purple (Fig. 6) and Arrangement in Pink, Red and Purple (Fig. 7) (both from 1883–84).11 The dress itself presents Whistler’s personal interpretation by tying it with a belt and reducing its width and length to show a petite figure. Whistler regularly stylized the sitter’s dress, especially in the 1880s when he became tired of the Aesthetic dress (probably too popular for his taste) and preferred more revealing and sophisticated silhouettes.12 His stylization of female clothes evinces interest in fashion and the possibility of manipulating fabric to fit his mental picture. Indeed, Milly Finch’s dress appears in several other works painted in different colors, as in Harmony in Blue and Violet (1881–87), Harmony in Fawn Color and Purple (1881–87), and Harmony in Coral and Blue (1881–87), among others. The dress acts as a screen on which the artist projects colors according to his fancy. The setting also contributes to this loose representation of the here and now. From August 1881 to October 1884, Whistler rented a house-studio at 13 Tite Street, where the scene that the watercolor captures likely took place.13 The purple background belongs to a backdrop covered by an ultramarine sheet with a purple fabric cascading on top. The watercolor Note in Pink and Purple–The Studio clearly shows the backdrop, placed behind the chaise longue in one corner of the studio, next to several canvases of different sizes. This device allowed the artist to quickly modify the chromatic environment of the scene in order to suit his mood.14

The chameleonic nature of Whistler’s depiction of the colors and arrangement of his studio resonates in the environments he devised for his exhibitions. In 1884, Whistler designed the first of his “Notes”–“Harmonies”–“Nocturnes” exhibitions, showing sixty-seven works (watercolors, oils, and pastels) in an Arrangement in Flesh Color and Grey, which combined painted architectural elements and draperies in silver, white, rose, and beige.15 It is possible that Milly Finch hung there, either under number six or ten (both titled Violet and Red).16 The fact that the exhibition would take place at Dowdeswell Gallery, instead of in the flagship Aesthetic Grosvenor Gallery, adds to the affront that his work posed to the waning Aesthetic movement. In 1886, Whistler restaged his “Notes”–“Harmonies”–“Nocturnes” at Dowdeswell’s with seventy-five works, now in an Arrangement in Brown and Gold.17 The apparent and mutable connection between the object of display and the site-specific chromatic environment corresponds to the indeterminacy with which Whistler rendered both the fan and the object on the table in this painting of Finch posed in his studio. The fan dramatically differs from the highly decorated Asian artifacts that Whistler depicted in works firmly associated with the Aesthetic movement before 1879. That year, the artist went bankrupt and had to sell all his personal goods, fans included. The fan, therefore, could be a cheap paper fan produced in Japan for export, or a replica of a male fan from the Edo period: somber, sometimes undecorated, and larger than the fans for female use, adding a layer of vulgarity or lack of lady-likeness.18 The yellowish object on the table might be a vague representation of the eight inch-tall plaster statuettes that Whistler used to model women in fashionable dress.19 In either case, the feminine form of this object establishes a parallel between Finch posing provocatively in fashionable dress and Whistler’s production of fashionable and provocative environments.

With Milly Finch, Whistler expressed his unique vision of art at the same time that he revealed a new set of alliances. As he wrote in 1885 in his “Ten O’Clock” lecture: “Art…is goddess of dainty thought—reticent of habit…seeking and finding the beautiful in all conditions, and in all times…”20 This statement seems to be referring as much to “Art” as to himself, pointing to his notion of dainty thought and his rejection of convention. By 1884, Whistler was consciously exploring both new aesthetics and themes that removed him from the tenets of his denounced critics, and that intended to shock the public and promote the sale of his work. The erotic tone of Finch’s pose, as well as the flared fan, the red chaise longue, and her red stockings, present a jarring image of a progressive, sexually provocative, and modern woman. But there are other elements that provide insights into his vision more generally—elements in which he found “the beautiful in all conditions, and in all times.” Asian culture is well-represented in the watercolor through the image of the fan, but also in the design of his butterfly signature. Photography was another source that fed his imagination, with the effect of a ghostly figure or a body caught in motion. Yet, this subject was also an interrogation of prior images of the reclining female nude—one whose sexuality is arranged through color and dress design. Industrial and artistic change did not scare Whistler as it did some of his critics. Rather, he welcomed new technologies, styles, and alliances, renewing certain elements of British Aestheticism and embracing Finch’s daring personality. Reality never escaped his desire for change and stylization as he bent it to fit into his world of dainty thought.

Bibliography

1 James McNeill Whistler to George A. Lucas, May 17/30, 1884, in Daniel E. Sutherland, Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 202.

2 Frederick Wedmore, “Mr. Whistler’s Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Gray,” The Academy 25, no. 629 (May 24, 1884), 374.

3 Anna Gruetzner Robins, “Whistler's New Portraits: Representing the Modern Woman,” in A Fragile Modernism: Whistler and His Impressionist Followers (New Haven: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2007), 80; and Aileen Ribeiro, “Fashion & Whistler,” in Whistler, Women & Fashion, by Margaret F. MacDonald, Susan Grace Galassi, and Aileen Ribeiro (New York: Frick Collection, 2003), 22.

4 Sutherland, Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 206.

5 Robbins, “Whistler's New Portraits: Representing the Modern Woman,” 84.

6 Stephen Hackney, “Art for Art’s Sake: The Materials and Techniques of James McNeill Whistler,” in Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice, edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 1995), 188.

7 James McNeill Whistler and Nigel Thorp, Whistler on Art: Selected Letters and Writings Of James McNeill Whistler (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 81–82.

8 Heather Mcpherson, “Manet: Reclining Women of Virtue and Vice,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 115, no. 1452 (1990), 34–44.

9 See Sarah Elizabeth Kelly, “Camera's Lens and Mind's Eye: James Mcneill Whistler and the Science of Art” (Columbia University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2010), chapters 4 and 5.

10 Kimberly Wahl, Dressed as In A Painting: Women and British Aestheticism in an Age of Reform (Durham, New Hampshire: University of New Hampshire Press, 2013), xi.

11 Margaret F. MacDonald, “Maud Franklin and the ‘Charming Little Swaggerers,” in Whistler, Women & Fashion, 147.

12 Wahl, Dressed as In A Painting, 39 and 46.

13 Daniel E. Sutherland. Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 181, 192.

14 The backdrop had wheels as can be seen in the photograph “James McNeill Whistler in his studio, 454a Fulham Road, London, with his portrait of Maud Franklin,” ca. 1886, albumen print. University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections, Whistler PH1/120; reproduced in Margaret F. MacDonald, “Whistler: Painting the Man,” in Whistler, Women & Fashion, photograph #1, p. 3.

15 Sutherland, Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake, 200.

16 James McNeill Whistler, ‘Notes’ – ‘Harmonies’ – ‘Nocturnes,’ exhibition catalogue. Tite Street, Chelsea, 1884.

17 Sutherland, Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake, 216–17.

18 Lionel Lambourne, “Fans, parasols, combs, pins, kimonos,” in Japonisme: Cultural Crossings Between Japan and the West (London: Phaidon, 2005), 112–116; and Julia Hutt, Ōgi: A History of the Japanese Fan = Nihon no sensu no rekishi: seiyō ni motarashita sono eikyō (London: Dauphin, 1992), 22.

19 MacDonald, “Maud Franklin and the ‘Charming Little Swaggerers,’” 155.

20 Whistler and Thorp, Whistler on Art, 80.