Pink Note–The Novelette, by Mary Okin

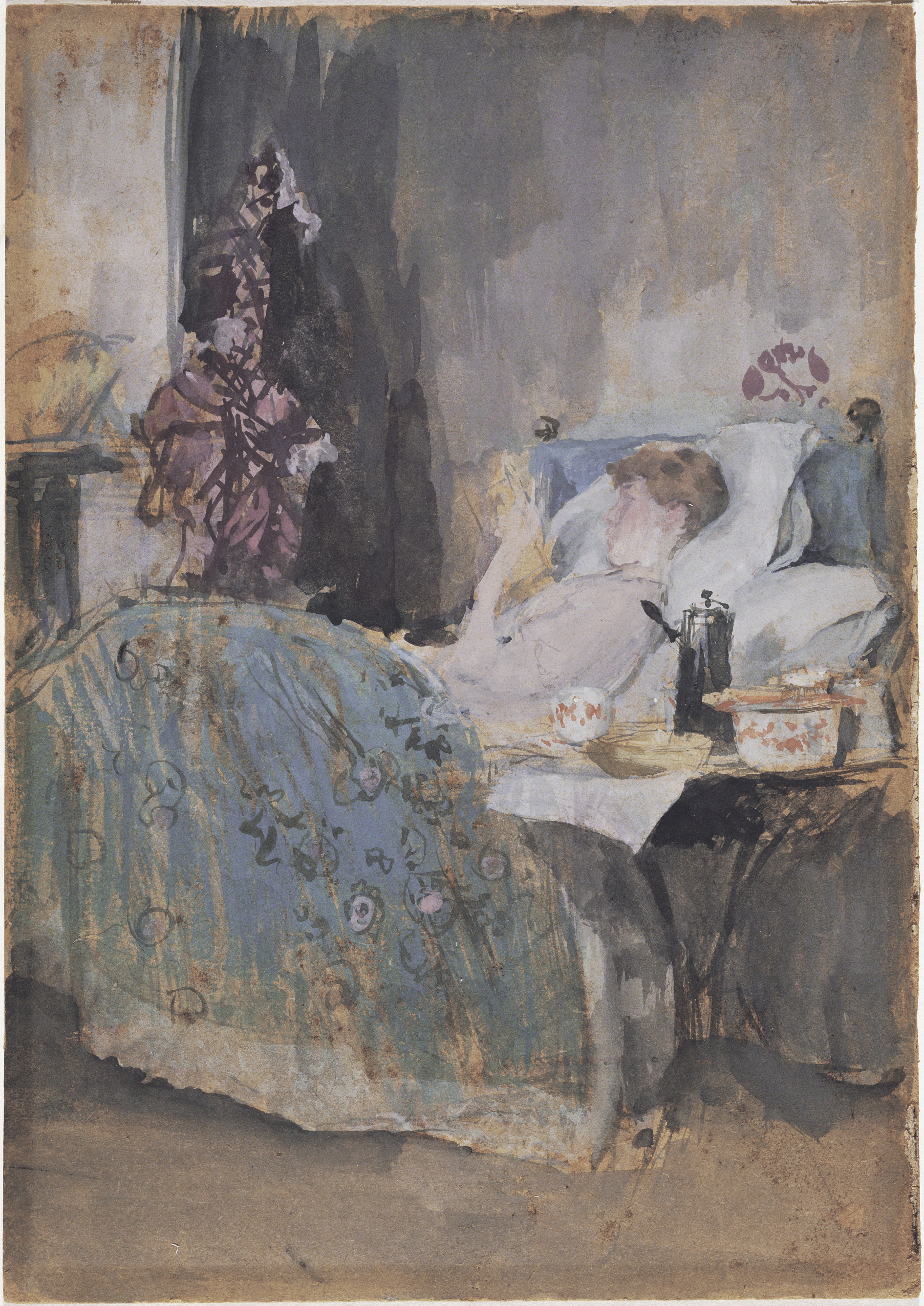

In Pink Note–The Novelette, Whistler’s gaze settles on the domestic space and his mistress, Maud Franklin (1857–1941), reading. The title tells us that the book she holds is a novelette, the French diminutive for a work of fiction shorter than a novel, longer than a novella, and popular among women readers in the late nineteenth century. Although theorizing the sensual nature of reading expressed in art would come much later in Western thought—what twentieth-century scholars borrowing from Walt Whitman and Rolande Barthes have characterized as the eroticism of words on the lips of the author transferring as pleasure to words on the lips of the reader, for example—Whistler already seems attuned to the sensual, sexual, and societal tensions that women’s pleasure reading elicits.1 At first glance, his reader appears passive, unaware of our presence. Yet, upon closer inspection, Whistler’s composition reconstructs a fleeting and more complex moment of shifting attention and worlds.

Indeed, the phenomenon of women reading presented an opportunity for Whistler to frame psychological tensions between men and women, domesticity and the decorative, in provocative ways, such as a seemingly artless moment of a woman reading and the artfully arranged objects framing that activity in Pink Note–The Novelette. Through Maud’s facial expression and pose, Whistler suggests a female reader so engaged with her book that she reads whenever possible. Her upright, seated posture at the foot of the bed indicates transience, rather than languishing, perhaps only moments before life or the man standing at the door interrupt her mind’s escape. This pose and her mental state are emphasized by vertical, wet-on-wet gray strokes of pigment on the upper left, delineating a darker corner of the room and creating an abstract element of negative space behind her. These strokes divide the composition in half and suggest a veil separating her from the space of the well-lit objects of home décor to her right. Maud seems to be pulled toward these objects and their arrangement by the blue-gray horizontal brushstrokes depicting a striped duvet—of similar tone and intensity to the book she holds. Meanwhile, the book anchors her temporarily and temporally to a world beyond our own.

If we embody Whistler’s gaze, our access to Maud is interrupted by a small table, which also appears in the watercolor Maud Reading in Bed (Fig. 1).2 Perhaps, this is a piece of furniture that can be attributed to Edward William Godwin (1833–1886), an architect and decorative designer who was part of Whistler’s inner circle. When Whistler returned to London from Venice in the early 1880s and began painting watercolors in earnest, Godwin acted as a promoter of this new work, whetting the public’s appetite for seeing Whistler’s watercolors when he reviewed London Bridge in 1881.3 In his own career, Godwin was busy creating Anglo-Japanesque designs that resemble the table in Pink Note–The Novelette, such as his 1881 Design for a Table (Fig. 2). The inclusion of such a table within Whistler’s watercolor paintings in 1883–1884 may be an expression of mutual admiration.

From the spindly legs of the Japanesque table and the remnants of its forgotten meal, Whistler draws our eyes to the delicate legs of the woman, relaxed and soft beneath a long gray skirt. The contrast of the stripes and darker gray washes of the duvet with the flatter color of Maud’s light gray skirt creates a line that draws our gaze upwards to Maud’s hands, the book they hold, and her minimally rendered, cherubic, heart-shaped face. A diagonal pattern of lighter colored areas—the white on the overhanging tablecloth that blends into the bedsheets to the right of Maud’s skirt and the white orb behind Maud’s head—also draws our gaze to Maud reading. The orb’s paint handling in white and earth gray is perhaps a depiction of a light source and a symbol of Maud’s intellectual engagement.4 Moving from the table in the opposite direction diagonally, our gaze is drawn from the tablecloth to the turned down bedding and up to the painting on the mantle, an object signifying Whistler’s intellectual engagement in this space.

Whistler expertly employed color within Maud’s jacket. The sleeve on Maud’s left arm, which draws our gaze to her face, appears a much lighter color than the rest of her jacket. This is the only purely pink “note” in the painting, made on Whistler’s palette by mixing zinc white with vermillion.5 We can more clearly see this pure pink sleeve as distinct from the muted, darker pink color—a mix of zinc white, vermillion, and other pigments—used on the rest of her jacket.6 Whistler’s choice of pure pink heightens our awareness of the contrasting green book occupying Maud, while it subtly divides her body into the colors informing the decorative harmony of Whistler’s composition.

This color harmony and tension of gray and pink held particular attraction for Whistler. In the spring of 1884, he designed Arrangement in Flesh Color and Grey, an exhibition at Dowdeswell Gallery, which displayed Pink Note–The Novelette and other watercolors in the Pink Note series for the first time.7 From a contemporary reviewer’s description, “the general effect of the room” created a “decidedly pleasing” atmosphere—words that call to mind Whistler’s interest in creating not just objects but immersive experiences for viewers.8 Whether a bedroom or a commercial gallery, Whistler conceived of space as a total work of art, meaning an interior’s architecture, furniture, wall and bed hangings, paintings, and objects created beauty through harmony in their arrangement.9 Harmonizing the watercolors within the 1884 exhibition involved “a dado of grey, and above pink oatmeal cloth—a very light and delicate shade of pink, stretched on the walls, against which were hung the pictures, or rather sketches, teamed in broad frames of bronze and silver.”10 At the private opening attended by Whistler’s invited guests, women were also treated to an aesthetically reinforcing performance—an “afternoon tea…served to the ladies by footmen attired in a grey and pink livery.”11 Pink Note–The Novelette thus pictures and participates in consumer culture, orchestrated both compositionally and materially in pink and gray by Whistler. Staging a woman in each of these contexts—Maud in the painting posed in this saleable and intriguing way, sitting amid all the trappings of aesthetic seduction, or the liveried tea for the aesthetic seduction of guests viewing the work—illustrates how Whistler was attuned to women’s lives and their consumerist and aesthetic practices. We might say he was a seasoned and astute voyeur and connoisseur.

Indeed, Whistler painting as voyeur and connoisseur is certainly an accurate description of this painting’s construction. Beneath the reading woman, the rumpled bed requires tidying from a man’s (Whistler’s) recent presence. Visual markers of his masculine possession are distinctively gray and pink. In addition to the Japanesque table already described, indistinct items on the bureau behind the bed are perhaps those pictured in the companion watercolor sketch, Resting in Bed (Fig.3). As recent scholarship asserts, the swath of pink atop the bedcovers is perhaps the very domino deployed to symbolize a man’s mistress in Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Black–Portrait of Theodore Duret (1883).12 These objects of dress occupy shared space casually and carelessly. In the background, a collection of pink and gray Japanese fans is artfully arranged around a pink and gray world-within-a-world painting. This Whistler-within-a-Whistler, surrounded by the exoticism of Japanese artifacts, seems curated for display. And the overall exhibition occurring within the composition—the used bed, the eaten meal, the painting on the mantle, the exotic fans above a cold fireplace, and Whistler’s pink colophon signature on the gray bedsheets—embodies the intrigues, tensions, markers, and moods of aesthetic and sexual arrangements. The objects hint that later in the day another meal will be eaten, another fire will be stoked, the bed and woman will be claimed, and a new painting will be inspired and, perhaps, exhibited.

And in this dance of attraction, the figure of Maud, who at first glance appears passive, retains autonomy through reading. Indeed, Pink Note–The Novelette engages with a long history of women reading in Western painting, which, prior to the eighteenth century, usually pictured devout women with scripture (e.g., images of the Virgin Mary communing with the Psalms). However, by the second half of the eighteenth century, when Jean-Honoré Fragonard painted A Young Girl Reading (1769) (Fig. 4) as part of his Fantasy Pictures series, popular fiction began contributing to a rise in women’s education and a new phenomenon in the nineteenth century: women reading for pleasure en masse.13 Pink Note–The Novelette captures a representative version of this psychosocial transition in culture, which also captivated a number of Whistler’s contemporaries.14 While socially progressive in capturing the freedom of women’s leisure reading, Whistler’s use of the French word novelette in the painting’s title does feminize the subject being read as popular, perhaps frivolous fiction, such as the French novels that were all the rage among middle- and upper-class women and among domestic servants in England.15 Indeed, a reviewer of the 1884 exhibition notes that Pink Note–The Novelette “represents a servant girl sitting on her bed reading a French novel.”16 As David Park Curry suggests, a particularly popular subgenre of French novels were fictional accounts of famous artists and their mistresses, a theme that might add a wash of pink pigment to the young woman’s cheeks.17

Women reading and especially women reading such books was not without controversy. In the nineteenth century, increasing numbers of women reading caused social anxiety about a woman’s rightful place in society, voiced by social conservatives who viewed preoccupation with books and pleasure reading as threatening in nature.18 If, for some, the ability to read was a marker of social standing and intelligence in women and an extension of the home, for others it was a potentially corrupting influence. To critics, allowing women to occupy worlds separate from their responsibilities to managing a household and a family, to religious faith, and to propriety, upset their duty to society and to men.19 Thus, women were watched for how and what they read.

To some extent, Whistler’s watercolor documents this change and its intrigues. Engaging intellectually and physically with someone else’s words, the young woman in Pink Note–The Novelette abandons her world for another’s—an impact Whistler sought to generate in viewers of his own work. The painting also documents Whistler’s disinterest in limiting a woman’s intellectual curiosity for the sake of family obligation or duty to domestic life, as the untidy room attests. Instead, Whistler depicts a woman finding pleasure in reading alone, a leisurely entertainment that, like the café-concert, the amusement park, the panorama, or the stereoscope, was part of a rapidly modernizing, industrializing, and increasingly secularizing London in 1884. At the edge of the sexual contract represented by the bed, the young woman reading appears resistant to society’s possession, but perhaps susceptible to an artist’s.

She also appears much younger than Maud’s twenty-six years, a blushing innocent even, if not for the objects surrounding her, which suggest the more titillating story of an artist and his mistress. In reality, Maud was entering the final years of her life with Whistler, the man who had seduced her and kept her as his model and mistress since her teenage years, by whom she had borne two children and fallen into convalescence as a result.20 “Mrs. Whistler,” as she sometimes called herself, spent a significant and turbulent majority of her youth (1873–88) being Whistler’s on-and-off-again household manager, travel companion, emotional support during and after the scandal of the Ruskin trial, and more. We might speculate how the novelette, a distraction establishing the distance between viewer and subject, already alludes to their eventual separation and her forced independence when Whistler wed Beatrice Godwin (Edward Godwin’s widow) without Maud’s knowledge in 1888.21 Or we might think about the ways in which Pink Note–The Novelette captures Maud’s resilience through convalescence and life with Whistler, and how her reading, an activity apart and all her own, interplays with an independence that was privately and publicly manifesting in this period. For example, Maud wrote business letters, she helped around the studio, and she studied art seriously alongside Beatrice Godwin, Mortimer Menpes, Walter Sickert, and others in the early 1880s.22 Around the time that Pink Note–The Novelette was first shown, she was also exhibiting paintings at the British Society of Artists under the pseudonym Clifton Lin, including portraits and flower paintings.23 In reading, she exists apart from Whistler and, eventually, in life as well.

Pink Note–The Novelette thus reconstructs an ephemeral world, a vignette in the fifteen years that was Whistler and Maud living together. It is a transference of an artist-lover’s gaze, inviting our own. It is a painting about women’s private lives and our consumption of such imagery. It is also a conceit offering a window into a reigning Aesthete’s private world that blends the intimate with a public staging for intended sale and consumption. A consummate voyeur and connoisseur, Whistler layers women’s intellect, the tensions of sexual desire, and the negotiations among the sexual contract, domestic management, and the freedom of leisure in ways that engage the history of women reading and the history of art. Between animate and inanimate decoration, repose and interruption, a used bed and the world beyond this bedroom, Pink Note–The Novelette pictures appetite and a historic turn. For such a rich vignette, sketchy strokes of pigment on watercolor paper depicting a woman about to turn a new page seem most appropriate.

Notes

1 James Conlon, "Men Reading Women Reading: Interpreting Images of Women Readers," Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 26, no. 2 (2005), 37–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4137395.

2 Godwin designed Whistler’s White House on Tite Street and they collaborated on Harmony in Yellow and Gold–The Butterfly Cabinet and other decorative furniture designs for the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris. For more on Maud Reading in Bed, see Katherine Roeder, “Domestic Interiors” in Whistler in Watercolor: Lovely Little Games (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2019), 203–215.

3 Lee Glazer, “A New Beginning,” in Whistler in Watercolor: Lovely Little Games (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2019), 16; for Godwin‘s review of London Bridge, see “Notes on Current Events,” British Architect 16 (September 23, 1881), 471.

4 Incandescent light had recently been invented in England by Joseph Swan, who began demonstrating his invention in 1880 and opened the first incandescent lamp factory in Benwell at the West End of Newcastle on Tyne in 1881. By 1883, incandescent lamps did include large round bulbs of similar shape to the orb behind Maud. However, although lamps of other shapes do appear in photos of Whistler’s studio by George Percy Jacomb-Hood from the early 1880s, there are no known records confirming that Whistler owned a round bulb lamp or that he used incandescent light during 1883–1884. For photos of Whistler's studio by Jacomb-Hood, see Glazer, Whistler in Watercolor, 53, 196. For, more on the invention, manufacture, and introduction of incandescent light to London, see Charlotte Fiell and Peter Fiell, 1000 Lights: 1878–1959 (Köln: Taschen, 2005).

5 Interview with Emily Jacobson, Paper and Photography Conservator at the Freer-Sackler, regarding pigment analysis of Pink Note – The Novelette, conducted on August 2, 2019.

6 According to Jacobson, pigment analysis to date and archival research has not indicated that Whistler used or purchased a commercially available gray watercolor pigment, preferring instead to make various shades of gray by mixing pigments on his palette. In Pink Note–The Novelette, ultraviolet analysis reveals that Whistler mixed zinc white with various colors to create gray or gray-tones, such as mixing zinc white with vermillion and other pigments to create the muted gray of Maud’s jacket. For more on pigment and paper analysis of Whistler’s watercolors, see Emily Jacobson and Blythe McCarthy, “Knowledge of a Lifetime,” in Whistler in Watercolor: Lovely Little Games, 110–141.

7 Kenneth John Meyers, Mr. Whistler’s Gallery: Pictures at an 1884 Exhibition (London: Scala Publishers, 2003).

8 “Gossip of the Clubs,” The Stroud Journal (Stroud), May 24, 1884.

9 The notion of gesamtkunstwerk, or a total work of art achieved through unity or harmony of decoration and design of interior space, was first articulated by the German composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner in relation to opera and refined by the French poet, essayist, and art critic, Charles Baudelaire, who, in part, inspired Whistler. Scholars of Whistler have argued that the total work of art is one way of understanding Whistler’s oeuvre, which includes not just the color harmony he sought within his painting or tonality within his prints, but his self-promotion, his domestic interiors, exhibition designs and publications, writings, collaboration with other designers (such as Godwin), decorative object collecting and display, and so on. See, Robert Jensen, Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-siècle Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 42–48.

10 “Gossip of the Clubs,” The Stroud Journal (Stroud), May 24, 1884.

11 Ibid.

12 Katherine Roeder, “Domestic Interiors,” in Whistler in Watercolor: Lovely Little Games, 212.

13 Kate Flint, The Woman Reader, 1837–1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

14 Other artists who took up this subject include Gustave Courbet, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, John Everett Millais, and Winslow Homer, among others.

15 David Park Curry, James McNeill Whistler at the Freer Gallery of Art (Washington DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1984), 197.

16 “Gossip of the Clubs,” The Stroud Journal (Stroud), May 24, 1884.

17 Curry, James McNeill Whistler at the Freer Gallery of Art, 197.

18 See, Jacqueline Pearson, “What Should Girls and Women Read?,” in Women’s Reading in Britain, 1750–1835: A Dangerous Recreation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); and Jennifer Phegley, “‘I Should No More Think of Dictating…What Kinds of Books She Should Read’: Images of Women Readers in Victorian Family Literary Magazines,” in Reading Women: Literary Figures and Cultural Icons from the Victorian Age to the Present (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006), 105–128.

19 Ibid.

20 Margaret F. McDonald, “Franklin, Maud,” in Dictionary of Artists' Models, edited by Jill Berk Jiminez (London: Routledge, 2013), 197–200.

21 Lee Glazer, Emily Jacobson, Blythe Ellen McCarthy, and Katherine Roeder, Whistler in Watercolor: Lovely Little Games.

22 Ann Koval, “The ‘Artists’ have come out and the ‘British’ remain: the Whistler faction at the Society of British Artists,” in After the Pre-Raphaelites: Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), 94–95, 109.

23 McDonald, “Franklin, Maud,” 197–200.