- Object Date

- Goryeo 고려 高麗 dynasty (918–1392), mid-fourteenth century

- Medium

- Hanging scroll mounted as panel; ink, color, and gold on silk

- Dimensions

- Image: 98.3 x 47.7 cm (38 11/16 x 18 3/4 in.)

Overall: 190.1 x 67.5 cm (74 13/16 x 29 9/16 in.)

- Credit Line

- Gift of Charles Lang Freer

- Collection

- Freer Gallery of Art

- Accession Number

- F1904.13

- Provenance

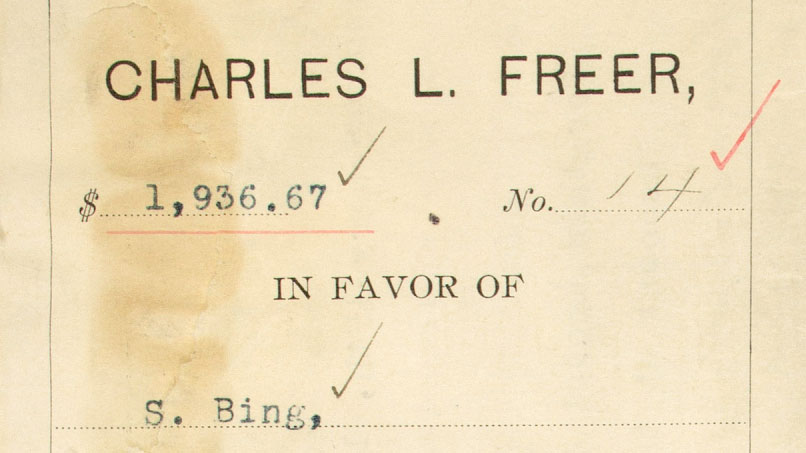

To 1902

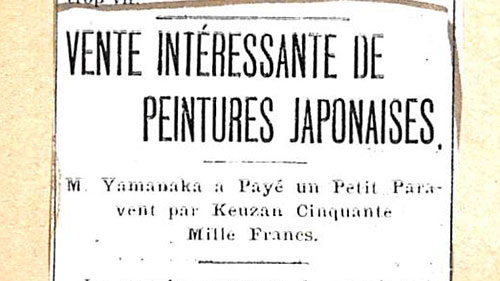

Yamanaka and Company, to April 15, 1902 [1]From 1902 to 1903

Charles Firmin Gillot (1853–1903), Paris, purchased from Yamanaka and Company on April 15, 1902 [2]From 1904 to 1919

Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), purchased through Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), from the sale of the Charles Gillot Collection, Paris, Galerie Durand-Ruel: Collection Ch. Gillot: objets d'art et peintures d'extreme-orient, February 8–13, 1904, lot 2004 (ill.) [3]From 1920

Freer Gallery of Art, gift of Charles Lang Freer in 1920 [4]Notes:

[1] A label accompanying the painting indicates that Charles Firmin Gillot purchased the painting from the Japanese dealer, Yamanaka and Company, on April 15, 1902. See also, Curatorial Remark 8 in the object record, which states, "A paper accompanying the painting seems to indicate that Gillot had purchased the painting from the Japanese dealer, Yamanaka, in 1902."[2] See note 1.

[3] See undated folder sheet note. See L. 31, Original Panel List, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. After Gillot’s death in 1903, a sale of his Asian art collection took place in February 1904 at the Durand-Ruel gallery in Paris. This object was purchased by Siegfried Bing for Charles Lang Freer at that sale (see Curatorial Remark 1 and Past Label Text 2 below).

[4] The original deed of Charles Lang Freer's gift was signed in 1906. The collection was received in 1920 upon the completion of the Freer Gallery.

- Past Label Text

Korean Art, July 15–September 15, 1981; by Ann Yonemura (shown with F1906.269)

Images of Avalokitesvara [Avalokiteshvara], the bodhisattva associated with compassion, shown with a willow branch and seated on a cluster of rocks near the water, are traditionally held to have first appeared in China during the T'ang [Tang] 唐 dynasty (618–907). Under the influence of Ch'an [Chan] 禪 (Kr. Seon, Jp. Zen) Buddhism, paintings of this subject became very popular, and many examples were carried from China to Korea and Japan during the Sung [Song] 宋 (960–1279) and Yuan 元 (1279–1368) dynasties.

This painting, executed in ink, color, and gold on silk, follows the same Chinese prototype as numerous other surviving examples executed during the late Koryo [Goryeo] 고려 高麗 dynasty. The willow branch is held in a small vase to the side of the bodhisattva. The small figure in a devotional pose may represent an allusion to a passage in the Avatamsaka Sutra. The details of this painting, from the elegant pose of the deity to the delicate use of color to render elements of the costume, are characteristic of Korean Buddhist painting at the peak of its development. Touches of gold highlight the landscapes in a typically decorative manner.

- Studies in Connoisseurship: 1923–1983, September 23, 1983–March 1, 1984; by Ann Yonemura (shown with F1906.269)

Purchased for Freer in Paris by Seigfried Bing at the 1904 sale of the Charles Gillot collection, this painting was listed in the section of Japanese paintings in the Gillot catalogue. There it carried an erroneous attribution to "Gōdo Ghen 吳道玄 (act. ca. 710–760)," the T'ang [Tang] 唐 dynasty Chinese painter Wu Tao-hsuan [Wu Daoxuan] 吳道玄 (Wu Tao-tzu [Wu Daozi] 吳道子), whose paintings are no longer extant. Despite the illogical attribution to a painter of the mid-8th century, the date proposed for the painting was of the mid-14th century. A paper accompanying the painting seems to indicate that Gillot had purchased the painting from the Japanese dealer, Yamanaka, in 1902.

In Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art, published in 1912, Ernest F. Fenellosa argued against the attribution to Wu Tao-tzu [Wu Daozi] 吳道子 (act. ca. 710–760) and described the painting in Freer's collection as probably a Sung [Song] 宋 dynasty painting reflecting the style of T'ang [Tang] 唐 painter Yen Li-pen [Yan Liben] 閻立本 (ca. 600–674). Fenellosa regarded the painting as a fine example belonging to the tradition of a famous Avalokitesvara [Avalokiteshvara] in the collection of the Japanese temple Daitokuji 大德寺, which was then attributed to Wu Tao-tzu [Wu Daozi] 吳道子, but is currently identified as a Korean Buddhist painting. Freer's collection inventory describes the painting as "copied in Japan during the XIV century, after a design by Go Doshi (Wu Tao-tzu [Wu Daozi]) 吳道子," and John Ellerton Lodge considered it to be an unimportant work later in date than Sung [Song] 宋. Only in 1965 was the painting identified by James Cahill, Curator of Chinese Art, as Korean, Yi 李 dynasty [also called Joseon 조선 朝鮮 period], 15th century.

Comparison to a number of recently published Koryo [Goryeo] 고려 高麗 dynasty paintings of Avalokitesvara [Avalokiteshvara] shows this painting to possess the style and iconography typical of late Koryo [Goryeo] 고려 高麗 Buddhist paintings. In recent studies by Japanese scholars such as Ueno Aki 上野秋, Koryo [Goryeo] 고려 高麗 Buddhist paintings have been shown to belong to a relatively limited repertoire of iconographic models. Most Korean representations of Avalokitesvara [Avalokiteshvara] follow a specific model, where the deity is seated in a rocky, cave-like setting overlooking water. Below the deity in the pond is a small holy child representing Sudhana, whose pilgrimage to visit many Buddhist deities is described in the Avatamsaka sutra. A bamboo grove appears in the background, and a branch of willow is held in a vase or bowl near the extended right arm of the figure.

Stylistically, the Freer painting is closely related to other surviving 14th-century Korean paintings of this subject, especially one in the Japanese temple Taizanji 泰山寺 in Kobe 神戸 city. Typical Korean stylistic features are the extensive gold highlighting of the undersurfaces of the oddly shaped rocks, the textile patterns on the robes of the figure, including the diaphanous gauze veil, and the double outlines on the red lower garment.

- Goryeo 고려 高麗 Buddhist Paintings: A Closer Look, February 25–May 28, 2012; by Keith Wilson (shown with S1992.11 and F1906.269)

Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (Suwol Gwaneum bosal 수월관음보살 水月觀音菩薩)

Korea, Goryeo 고려 高麗 dynasty, mid-14th century

Hanging scroll mounted as a panel; ink, color, and gold on silk

Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1904.13A primary attendant of the Buddha Amitabha, Avalokiteshvara is also worshiped independently as the bodhisattva of mercy. Here the deity—wearing a patterned gauze wrap over flowing garments—sits in a relaxed manner on a rocky outcrop at Potalaka, his island home. This type of image, which first appeared in eighth-century Chinese paintings, is called "Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara" because most examples show the moon and its reflection in the water at the base of the island. In this painting, however, the presence of the moon is more lyrically expressed through golden highlights that suffuse the landscape. The small child in the lower left corner is the young pilgrim Sudhana, who was sent to visit Buddhist bearers of great wisdom.

Goryeo 고려 高麗 Buddhist Paintings: A Closer Look

Inspired by subjects and compositions originating in China, these religious icons illustrate a distinctly Korean achievement that was not duplicated elsewhere in East Asia.Buddhism was introduced to the Korean peninsula by Chinese monks in the late fourth century CE. Within two hundred years, the faith was flourishing under court patronage that lasted nearly a millennium. These three paintings [S1992.11, F1904.13, and F1906.269] were created during the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, toward the end of this long era of royal support. Not made for grand temple halls, in which monumental murals were painted directly on the walls, these detailed images were intended for closer viewing in more intimate settings.

All of the icons in this gallery promise salvation, release from the karmic cycle, and rebirth in a Buddhist heaven, or “Pure Land.” Modern scholars believe that these images were produced both to aid private meditation and to symbolically guide mortal souls to paradise at death. For both functions, the works would have been displayed in close proximity to the believer.

The paintings’ visual appeal results from precise draughtsmanship, saturated mineral pigments, extensive use of gold, and detailed designs representing woven textile patterns. The painters added depth by simulating transparency and translucency, both by adjusting color values—as seen on Kshitigarbha’s “wish-granting jewel” and Avalokiteshvara’s crystal beads—and superimposing gauzy fabrics executed with fine networks of thin white lines. To model surfaces and make them appear more three-dimensional, the artists experimented with applying pigment to both sides of the silk surface, allowing the viewer’s eye to blend the colors and visualize more rounded forms.

- Remarks

(Undated Folder Sheet note) Bought by Mr. Bing for Mr. Freer at the Gillot sale in Paris, February 1904 (Gillot no. 2004). Received as a kakemono 掛物; later mounted in panel form. For price, see L. 31, Original Panel List.

(Undated Folder Sheet note) Original attribution: "Copied in Japan during the 14th century after a design by Go Doshi 吳道子 (Ch. Wu Daozi)." Later, corrected description: “Artist unknown. Period uncertain.” See further, S.I. 1, Panels, Inventory, and (rescribed) in Envelope File.

(John Ellerton Lodge, 1921) Looks Chinese, on the whole, and if so—may be Ming 明, or even Yuan-Ming 元明 work—suspicious that it may be Japanese, though I doubt it. Coarse work—not important.

(Undated Folder Sheet note) Remounted by Yokichi Kinoshita 木下容吉 in 1933.

(H. Elise Buckman, 1963) The following is incorporated from the Envelope File [Original note pasted in object file]: “Painted on silk, in colors and gold. Without signature or seal. Received as a panel and still remains in that form.” [See also Curatorial Remark 1.] The Envelope File has now been destroyed.

(James Cahill, 1965) The attribution should be changed from "Chinese, Yuan-Ming 元明 (?)" to "Korean, Yi 李 dynasty [also called Joseon 조선 朝鮮 period], 15th century."

(Ann Yonemura, 1981) Exhibition Korean Art label text; moved to label field.

(Ann Yonemura, September 1983) Exhibition Studies in Connoisseurship: 1923–1983 label text; moved to label field.

(Jeffrey Smith, Louise Cort, and Soo Yeon Park 박수연, July 26, 2010) As of this date, the Romanization of Korean period names, place names, and ware names in the ID-related fields of TMS is changed from the McCune Reischauer (MR) system to the Revised Romanization of Korean (RR) system, established in 2000 by the Ministry of Culture, Republic of Korea. From this point onward, new curatorial comments, exhibition labels, and other entries should use the RR system. Previous curatorial comments have not been revised.

(Louise Cort, March 16, 2011) The remainder of Charles Gillot's collection, which had been bought back by his widow at the 1904 sale and kept in his family, was sold at Christie's Paris, March 4–5, 2008, sale number 5540. An article by Souren Melikian comparing the reception of the original sale and the recent one appeared in the New York Times, March 7, 2008.

(Louise Cort, March 16, 2011) This image is of the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara, in Korean Suwol Gwaneum 수월관음 水月觀音.

(Jeffrey Smith per Keith Wilson, February 27, 2012) Late Goryeo 고려 高麗 dynasty, mid-14th century, from Sackler Goryeo exhibition label.

(Louise Cort, March 22, 2012) On the basis of images and object records sent to the National Museum of Korea, curator Park Hye-won 박혜원 notes that this painting is important.

- Published References

Galeries de MM. Durand-Ruel. Collection Ch. Gillot: Objets d'art et peintures d'Extreme‑Orient. Paris: Galeries de MM. Durand-Ruel, 1904. 223, 266, lot #2004.

Fenollosa, Ernest Francisco. Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design Vol. 1. London: W. Heinemann, 1912. Next to p. 122.

Fenollosa, Ernest Francisco. Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design Vol. 1. New York: F.A. Stokes Co.; London: W. Heinemann, 1921. Next to p. 122.

Park, Edward. Treasures from the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983. 360.

Yonemura, Ann. “Korean Art in Western Collections 5: Korean Art in the Freer Gallery of Art.” Korean Culture 4, no. 2 (1983): 4–15.

Lawton, Thomas. Freer: A Legacy of Art. Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution; New York: H.N. Abrams, 1993. 123, fig. 84.

Kikutake Junichi 菊竹淳一 and Chung Woothak 鄭于澤, eds. Goryeo sidae ui bulhwa 高麗時代의 佛畵 [The Buddhist paintings of Koryo dynasty]. Seoul: Sigongsa, 1997. Vol. 1: 190–91, pl. 88; Vol. 2: 95–96.

Kikutake Junichi 菊竹淳一 and Chung Woothak 鄭于澤, eds. Kōrai jidai no butsuga 高麗時代の仏画 [The Buddhist paintings of Koryo Dynasty]. Seoul: Sigongsa, 2000. 190–91, 454, pl. 88.

Lippit, Yukio. “Goryeo Buddhist Painting in an Interregional Context.” Ars Orientalis 35 (2008): 203, fig. 5.

Fitzhugh, William, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch, eds. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. Media; Dino Don: Mongolian Preservation Foundation; Washington, DC: Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution, 2009. 243, fig. 32.5.

Foxwell, Chelsea. “’Merciful Mother Kannon’ and Its Audiences.” The Art Bulletin 92, no. 4 (December 2010): 329, fig. 3.

Chung Woothak 정우택. “Miguk sojae Hanguk bulhwa josa yeongu 미국소재 한국불화 조사 연구 [Investigation Research on the Korean Buddhist Painting in the United States].” Dongak misulsahak 東岳美術史學 13 (2012): 42, fig. 9.

Freer Gallery of Art. Korean Art in the Freer and Sackler Galleries. Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2012. 128–31, 134–35, pl. 7.1, 7.4.

- Restrictions & Rights

- Copyright with museum