Goryeo Buddhist Painting: Materials, Techniques, and Mountings

Korean Buddhist scroll paintings were traditionally painted on a fabric support with pigments made from natural materials using animal protein-based glues as binders. Due to changes in patronage, however, different periods are marked by distinctive materials as well as painting and mounting techniques. Current research reveals that luxurious materials were used for Buddhist scroll paintings produced during the Goryeo 高麗 dynasty (918–1392), when the court and aristocratic families supported Buddhism, while lower quality materials were used during the subsequent Joseon 朝鮮 period (1392–1910).

Fabric Support for Goryeo and Joseon Buddhist Paintings

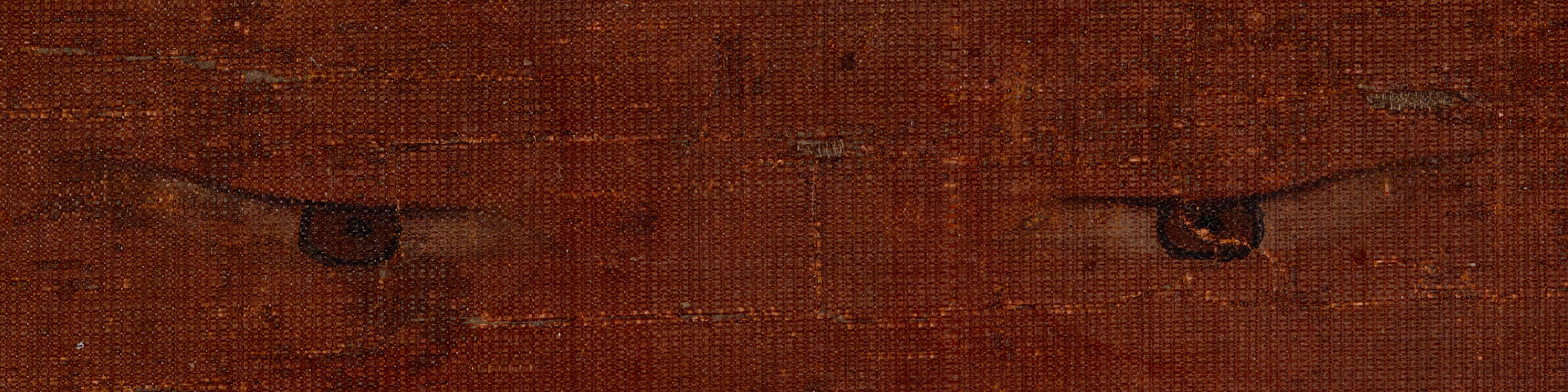

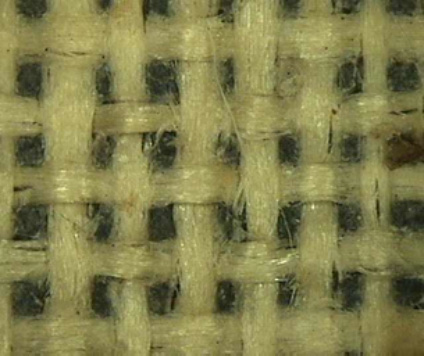

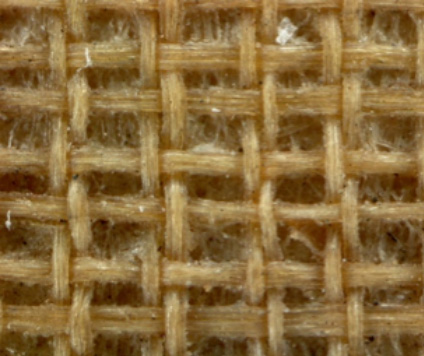

Over the years, silk, linen, hemp, and cotton were used as support materials for Korean Buddhist scroll paintings. During the Goryeo dynasty, tightly woven fine silk was the fabric of choice for color stability and the finest quality. The silk used for Goryeo Buddhist paintings was woven exclusively for that purpose. It was a plain weave produced with raw, unwashed silk. Unlike typical plain weaves (fig. 1), however, the silk used for Goryeo Buddhist paintings had double warps (fig. 2). This enabled the creation of a strong, high-quality support that was even and flat, which made it perfectly suitable for applying pigments. Virtually all surviving paintings—even comparatively large ones over two meters in width—were executed on a single piece of cloth without vertical joints. This special kind of silk must have been woven at dedicated workshops with advanced looms and weaving techniques by professional masters who specialized in Buddhist art production.

During the subsequent Joseon period, Buddhist scrolls were painted on various support materials ranging from silk, linen, and hemp to cotton. This was the result of several factors. First, court and aristocratic support for Buddhism largely ended with the fall of the Goryeo dynasty, which created a difficult financial situation for Korean Buddhist temples. In the end, materials supplied by commoners were used, resulting in a variety of fabrics for works sponsored by ordinary people. In addition, given the expansive size of Joseon Buddhist paintings, a much wider support was needed, and joints were unavoidable; even the widest widths of the earlier silk looms were insufficient. Due to the narrower loom widths, Joseon paintings created on fabric supports were typically pieced together.

Pigments in the Goryeo and Joseon Periods

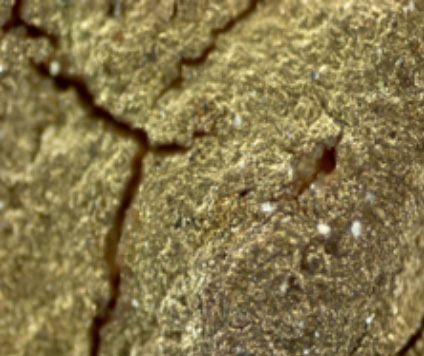

Korean Buddhist paintings usually include the colors red, green, blue, white, and yellow. Red is typically vermilion (mercury sulfide [HgS]; fig. 3), but lac, a resinous secretion of insects, is also found. Malachite for green (fig. 4) and azurite for blue (fig. 5) are both mineral pigments derived from copper (Cu). These pigments oxidized over time, causing damage to the fabric support layer and darkening the color of the backing paper to brown. In extreme cases, entire areas of original green pigment have separated and fallen off. “Lead white” and white clay were used for white pigment (fig. 6). Both possess fine particle size and good adhesive strength with other pigments.

Gold played a particularly important role in Buddhist art and was used in two ways: gold leaf and gold powder. Gold leaf was produced by beating gold until it was thinner than paper; gold powder was ground even more finely and used like a pigment, which was applied with a brush (fig. 7). Gold powder was used far more widely than gold leaf in Goryeo Buddhist paintings. This gold powder had a very fine particle size and was extremely useful in the depiction of delicate patterns.

The preservation of the gold on the surface of paintings depends upon the pigment lying beneath it. Many gold lines applied over green are damaged or missing but are still vivid in red areas. The crystals comprising the green malachite pigment are large and coarse, which cause them to separate relatively more easily from the surface. Mercury sulfide (vermillion), on the other hand, yields a red with fine, condensed particles and a strong binding power, thus enabling the long-term survival of the gold painted on top.

In Goryeo Buddhist paintings, gold was used not only for textile patterns but also for the skin color of various deities. In Joseon Buddhist painting, however, the yellow pigment orpiment, or arsenic sulfide (As2S3), was sometimes used in areas representing skin and decorative patterns, instead of expensive gold.

Goryeo Buddhist Painting Technique

Finished Goryeo Buddhist paintings on silk were based upon preliminary ink-brushed designs. Before the ink sketch was painted, the silk support was fixed tight on a wooden frame. Sizing could then be evenly applied to both the front and back surfaces. After the sizing had dried, Chinese ink was used to create the outline and details of the desired design on the front face of the silk.

Although we cannot confidently reconstruct the specific methods used to produce Goryeo Buddhist paintings due to the passage of time, it is possible to offer some logical observations on the creative process. First, it appears that there were two ways ink-brushed designs could be prepared for a desired painting: It could be brushed directly on the face of the silk, or a sheet of paper with the ink-brushed design could be attached to the back of the silk support. In either case, these outlines determined how the finely ground pigments were applied on the back face of the silk. Because the fabric used for such paintings was thin enough to be transparent, color applied to the back appears as a softer and more subdued color on the front. In general, the areas chosen for back painting were the exposed flesh of the deities as well as some larger sections, such as garments (fig. 8). In a number of paintings, back painting was more elaborate, with different pigments applied to supply greater detail.

After pigments were applied to the reverse, the colors added to the front surface yielded enhanced visual effects. At this point, the original ink sketch lines were no longer visible. As a result, new lines were needed to demark contours and define constituent elements of the composition. These new lines, which are still visible to viewers today, were drawn in color or gold pigment instead of black ink.

Mounts during the Goryeo and Joseon Periods

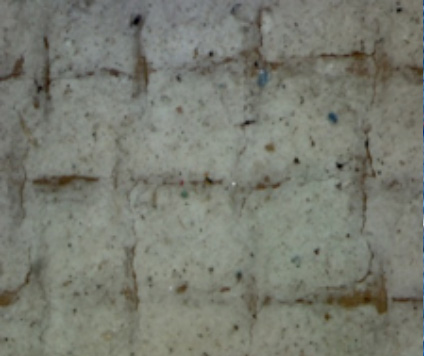

East Asian Buddhist scrolls and screens, unlike Western paintings, were created on a thin, weak support layer, such as silk or paper. To both strengthen and prolong the life of these works, several layers of paper were glued with wheat paste to the back of paintings. Patterned silks were then added to decorate and frame the painting, which could be made as either a scroll or screen. The chosen format for a mounting depended upon the purpose of the work as well as the size of the building in which it would be displayed.

Over time, East Asian scrolls and screens often deteriorated or became damaged and needed to be repaired. In such instances, old backing paper, which may have darkened, was removed and replaced by new, durable backing paper. Alternatively, only the framing silks may have needed replacement for the long-term survival of the painting. The Goryeo Buddhist paintings that have survived must have been repaired multiple times.

The Korean mounting style that was in use when the paintings were first produced has been lost. After having survived for six or seven hundred years, most of the Goryeo Buddhist paintings known today reside in Buddhist temples and museum collections in Japan, and thus have been remounted in a Japanese style. Many Goryeo Buddhist scroll paintings—primarily those in Western collections—have been trimmed on the top and bottom and attached to wooden stretchers for ease in storage and exhibition. These alternative styles have made it difficult to understand the original manner of Goryeo Buddhist painting mounts.

Fortunately, a painting of Fifteen Thousand Buddhas (fig. 9), kept in the Fudoin 不動院 in Hiroshima, Japan, survives with traces of painted mountings of Buddhas, which suggests that Goryeo paintings could have been finished with painted borders. It is thought that unlike other kinds of painting, Korean Buddhist works were given painted borders that were created when the painting itself was produced. Called “painted mountings,” this is the most convenient and rational way to produce the main subject and its decorative frame at the same time.

However, the practice of using painted mountings is more frequently encountered among Joseon period Buddhist paintings, most of which are scroll paintings made for temples (figs. 10 and 11). Unlike secular paintings, Joseon Buddhist paintings were decorated by painting the borders at the same time as the painting.